The release of large open-weight models like Llama 3, Mixtral, and others fundamentally shifted the self-hosted AI infrastructure conversation. Teams can now deploy powerful, commercially viable models in their own infrastructure without vendor lock-in, per-token pricing, or hyperscaler API dependencies.

For DevOps teams and platform engineers, this represents a genuine opportunity to deliver AI capabilities directly to their organizations.

Yet here's what we consistently observe in the field: teams approach open-weight model deployment with the same operational frameworks they've used for stateless web services and traditional infrastructure workloads. They estimate inference latency with a few benchmarks, check their GPU inventory, and declare themselves ready.

This confidence persists for approximately two to four weeks into production, at which point reality catches up with optimism. The infrastructure they thought was sufficient becomes a constant constraint. The operational complexity they didn't anticipate begins consuming engineering cycles. The machine learning expertise they assumed they could acquire on the job becomes a critical blocker.

Most teams, despite having modern DevOps practices and strong infrastructure foundations, discover they are profoundly underprepared for running production open-weight models at any meaningful scale.

This unpreparededness isn't a reflection of incompetence. It's the natural consequence of a significant skill and knowledge gap between traditional infrastructure operations and machine learning inference.

Open-weight models introduce operational challenges that don't map neatly onto containerization best practices or standard monitoring frameworks. The GPU becomes something fundamentally different from the compute resources that drove conventional scaling decisions. Memory management transforms from a solved problem into a daily operational concern. Failure modes become exotic and difficult to diagnose.

Understanding this readiness gap is essential before committing resources to open-weight models. Acknowledging the gap allows teams to make informed decisions about how to bridge it.

Some teams have the appetite and resources to build specialized capabilities for in-house deployment. Most teams would benefit from a realistic assessment of what deployment actually requires and what alternatives exist.

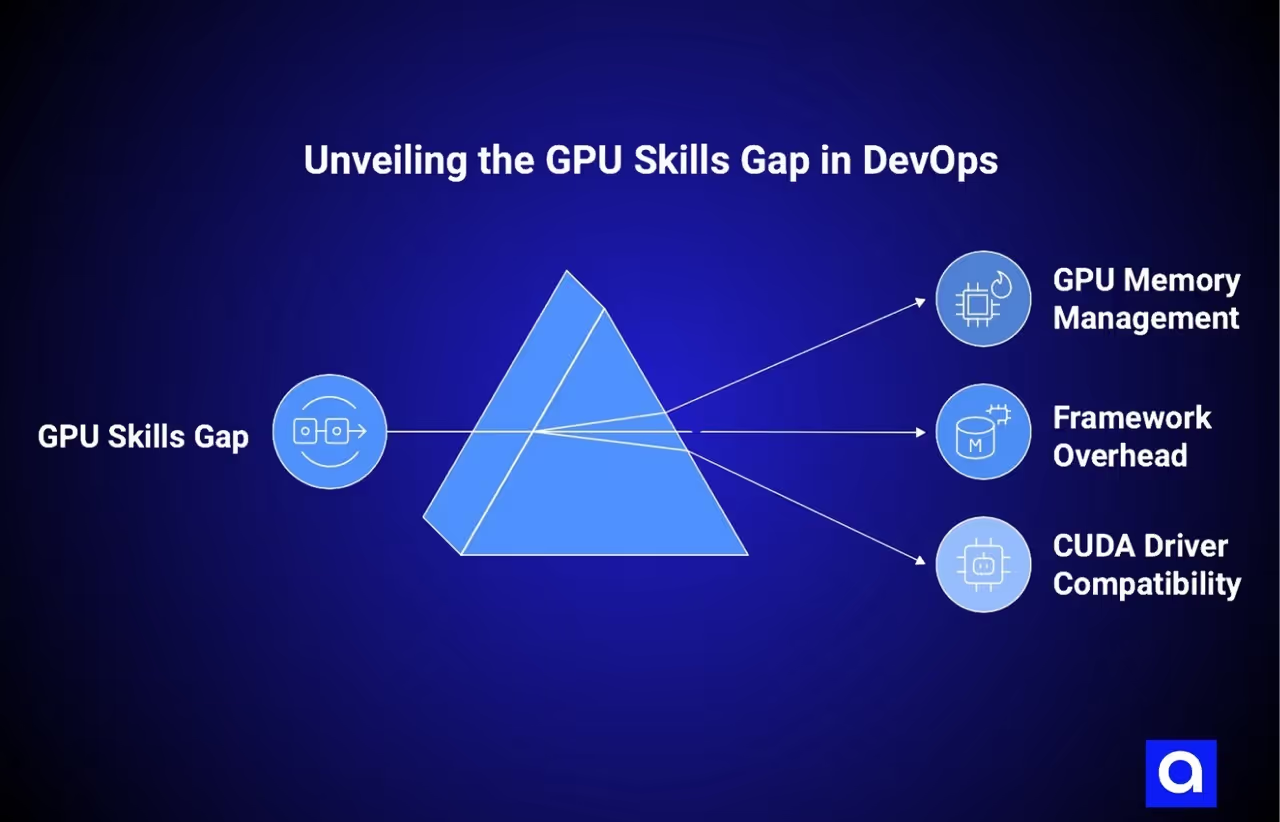

GPU Management and ML Skills: What’s The Critical Gap in DevOps Teams?

The first and most underestimated challenge is the skills gap between conventional DevOps expertise and the specialized knowledge required for open-weight model deployment.

When you deploy a containerized web application, you work within well-established paradigms. You understand how CPU and memory allocation work. You know how to measure application performance, set resource limits, and predict scaling behavior.

These mental models break down almost entirely with GPUs and inference workloads.

GPU memory management is perhaps the most immediately disorienting challenge. On CPU systems, memory overcommitment has graceful degradation through swap. On GPUs, memory overcommitment results in immediate, catastrophic failure. A model that requires 24GB of VRAM cannot run on a 16GB GPU, period. There is no graceful degradation, no spilling to slower storage. The model either fits entirely in GPU memory or it doesn't, and this simple fact cascades through infrastructure planning.

Teams must precisely calculate memory requirements not just for model weights, but for activations, gradients if fine-tuning is involved, KV cache allocations for different sequence lengths, and overhead from the inference framework itself.

Different frameworks introduce different overheads. A model that requires 20GB in pure VRAM might need 25GB with vLLM's overhead, or 27GB with TensorRT-LLM depending on batch size and optimization choices. Getting these calculations wrong means getting production wrong.

CUDA driver compatibility introduces another dimension of complexity that seasoned DevOps teams typically encounter for the first time.

Unlike CPU environments where driver versioning is largely abstracted, CUDA has a strict compatibility matrix between GPU hardware, driver versions, CUDA toolkit versions, and inference frameworks. A CUDA 12.0 application won't run on a CUDA 11.8 driver. A model optimized with TensorRT 8.6 might have unexpected behavior on TensorRT 9.0.

These aren't theoretical concerns—they manifest as production outages. Teams suddenly need to understand semantic versioning in CUDA, test model behavior across driver versions, and maintain explicit version pinning practices.

This becomes exponentially more complex when you're running multiple models with different framework requirements on the same infrastructure, or when you need to update drivers for security patches without breaking production inference.

The choice of inference framework itself represents a skill gap that most teams don't anticipate until they've already made a choice they later regret. vLLM has become the de facto standard for open-weight model serving, and for good reason. Its paged attention mechanism and continuous batching approach deliver significant efficiency gains.

But vLLM is a relatively new project, its API is still evolving, and deploying it at scale requires understanding paged attention semantics, memory pool management, and how batch composition affects throughput and latency tradeoffs.

TensorRT-LLM offers significantly better performance for certain models and hardware combinations, but it requires NVIDIA's compilation toolchain and GPU-specific optimization decisions.

Text Generation Inference (TGI) has its own set of tradeoffs. The choice between these frameworks isn't a simple "pick the best one" decision. It requires understanding your specific workload, hardware, and performance requirements well enough to make an informed evaluation. Most teams don't have that expertise in-house and can't easily acquire it. Organizations evaluating their readiness should assess their position across the full MLOps platform landscape before committing to self-hosted infrastructure.

Beyond framework selection, there's the entire domain of inference optimization that separates teams that run models competently from teams that run them efficiently. Quantization decisions (int8 vs int4 vs mixed precision) have dramatic implications for memory utilization and inference speed, yet the right choice is highly dependent on model architecture, hardware, and accuracy tolerances.

Prompt caching strategies can reduce latency and cost by 40-60% for workloads with repeated prefixes, but implementing them correctly requires architectural changes to how applications query the inference server. Context window optimization decisions affect both throughput and latency. Flash Attention 2, Paged Attention, and other modern inference techniques have specific requirements and tradeoffs that need to be understood.

A team without ML systems expertise will make suboptimal decisions in all of these areas, then wonder why inference costs are 3-4x higher than expected, or why latency is unacceptable despite having "plenty" of GPU capacity.

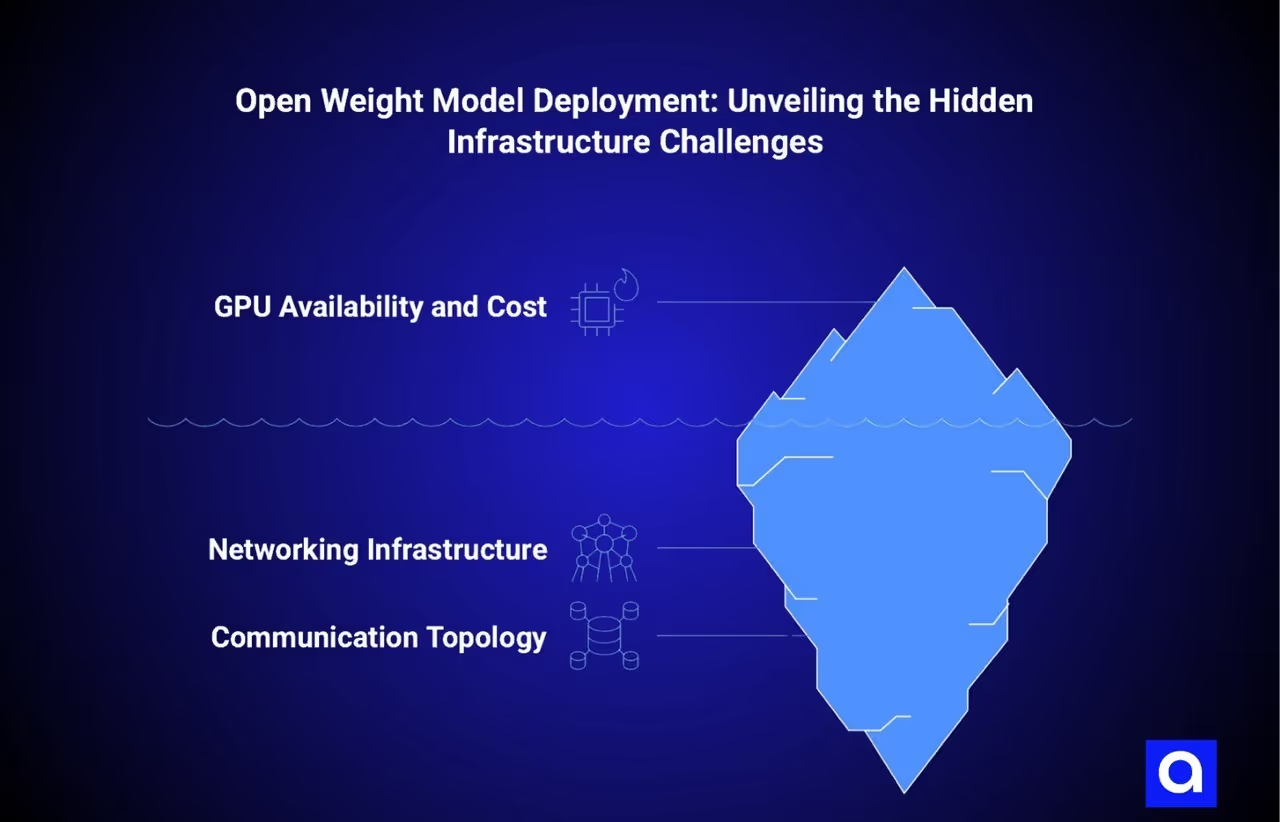

Infrastructure Requirements for Open Weight Models Exceed Standard Practices

Beyond the software skills gap, the physical infrastructure requirements for open-weight model deployment exceed what most teams have actually built out, even teams with sophisticated infrastructure foundations. This becomes especially acute when moving beyond toy deployments to real production workloads at meaningful scale.

The constraint that catches most teams first is GPU availability and cost. For teams pursuing self-hosted AI, standard cloud GPU pricing has become extraordinarily expensive.

An NVIDIA A100 with 40GB of memory costs roughly $3-4 per hour on-demand in major cloud regions. Running 10 of these continuously costs $72,000-96,000 per month. For a small or medium organization, this is a budget line item that didn't exist last year. Worse, GPU availability in public cloud regions has become spotty. When you need 20 A100s or H100s for production deployment, getting that allocation can take weeks or months.

Teams discover they need to think about GPU procurement in ways that mirror traditional data center hardware planning, with lead times and inventory management concerns that software engineers haven't dealt with in years.

The networking infrastructure for distributed inference also exceeds what most teams have properly architected. In our work with clients, we've seen that scaling beyond single-GPU deployments introduces critical networking constraints. When running inference on a single GPU or small cluster, networking is largely transparent. But as soon as you scale to distributed tensor parallel or sequence parallel inference, intra-cluster networking becomes critical.

A 176B parameter model run with tensor parallelism across 8 A100s generates hundreds of gigabytes per second of all-to-all communication between GPUs. If your cluster is connected via standard 1Gbps or even 25Gbps ethernet, the network becomes the bottleneck and communication overhead destroys the benefit of parallelization.

Production deployments at any real scale need NVLink (GPU-to-GPU over PCIe) or InfiniBand for node-to-node communication. Most on-premise data centers don't have this infrastructure. Most cloud providers don't have it available except in specialized regions or with dedicated clusters that cost substantially more.

Understanding the communication topology of your inference approach and matching it to your actual network infrastructure is a skill that most DevOps teams don't have.

Storage architecture for models introduces requirements that don't map onto traditional storage patterns. A 70B parameter model is roughly 140GB on disk in fp16 precision. A 405B model is over 800GB. Teams working with top open-source LLMs like Llama 3.1 405B need robust storage architectures that can handle these massive model files efficiently. When you're running dozens of inference servers or need to support model rotation, you suddenly have terabytes of model data that needs to be available with acceptable latency.

Network file systems like NFS or shared storage like EBS can work, but they introduce I/O bottlenecks and architectural complexity. Container images with embedded model weights become impractical at this scale. Teams need to think about model distribution, caching strategies, and cold-start behavior in ways that are entirely novel.

We've observed that a model taking five minutes to load from network storage turns the entire inference service into something with unacceptable availability characteristics. Getting model loading infrastructure right requires careful planning and architectural decisions that most teams won't anticipate until they're in production trying to troubleshoot why model serving is slow.

The power and thermal infrastructure required for GPU clusters has surprised many teams. Eight A100 GPUs in a single server consume roughly 5-6 kilowatts of power under full load. This isn't something you can just plug into a standard data center rack without proper planning. Cooling these systems requires dedicated cooling infrastructure, proper airflow management, and monitoring of thermal conditions.

Teams that have run traditional CPU infrastructure find that GPU infrastructure requires a different category of data center partner and support contract. For on-premise deployments, the implications are even more dramatic. You may need to upgrade electrical infrastructure, install additional cooling capacity, and redesign physical rack layouts. These costs aren't usually captured in the initial planning, but they're real and they're expensive.

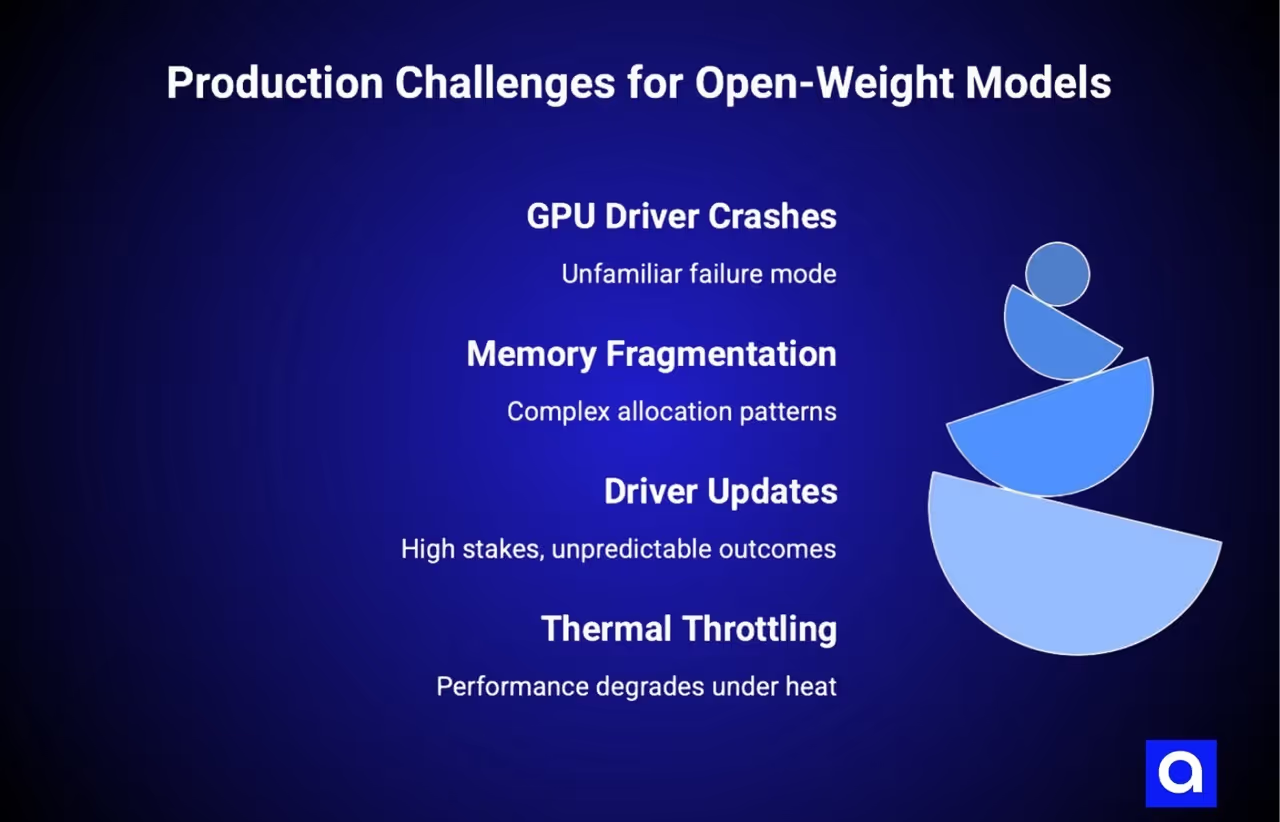

Production Challenges: GPU Failures, Memory Issues, and Thermal Management

As teams begin running open-weight models in production, they encounter failure modes and operational challenges that don't have direct analogues in traditional infrastructure operations. These challenges emerge as load increases, time-of-day variations affect utilization patterns, and the cumulative effect of edge cases becomes apparent.

GPU driver crashes and CUDA out-of-memory errors represent failure modes that are unfamiliar to most DevOps teams. A traditional application that runs out of memory will either be terminated by the operating system or fail gracefully. A CUDA out-of-memory error often cascades into driver instability, GPU resets, or complete node failure. Sometimes the GPU continues to function but becomes flaky and unreliable, returning incorrect results without surfacing errors.

Unlike traditional application failures that are straightforward to observe and remediate, GPU failures often require specialized knowledge to diagnose and fix. You need kernel logs, GPU telemetry, driver compatibility information, and understanding of CUDA semantics to determine what went wrong.

A team without GPU expertise will often spend hours troubleshooting what an experienced ML systems engineer would recognize instantly as a known driver issue or CUDA version incompatibility. This is where partnering with experienced AI development companies can provide the specialized troubleshooting expertise that most internal teams lack.

Memory fragmentation is another operational challenge that traditional DevOps teams don't encounter at the same scale. When running inference with various batch sizes and sequence lengths, GPU memory allocation patterns become complex. A model that served requests perfectly well with batch size 4 might fail with batch size 8 due to memory fragmentation, even though the total memory required is less.

Inference frameworks have different strategies for managing memory fragmentation, and the interaction between framework-level memory management and system-level memory allocation introduces subtle failure modes.

Teams will sometimes observe that adding more GPU memory doesn't help performance because the fragmentation pattern prevents efficient utilization. Resolving these issues requires understanding memory layout, batch composition strategies, and potentially framework-specific configuration tuning.

Driver updates and system patches introduce a dimension of operational risk that most DevOps teams haven't had to manage. Updating a server's OS typically is a straightforward operation with clear testing and rollback procedures. Updating GPU drivers has much higher stakes and much less predictable outcomes.

A driver update that has no effect on the host OS might break CUDA compatibility, introduce new performance characteristics, or even render certain models unable to load. Testing driver updates requires a test environment with identical hardware and software stacks, something that's expensive and often impractical.

Many teams end up with a "if it's working, don't touch it" mentality around driver versioning, which creates security risks and eventually becomes unmaintainable. The operational cost of maintaining driver versions, testing updates, and coordinating driver changes with framework updates is significant and often underestimated.

Thermal throttling and sustained utilization management introduce another set of operational challenges. When a GPU approaches its thermal limit, it reduces its clock speed to prevent hardware damage, causing performance to degrade.

High-performance inference workloads can drive GPUs to these thermal limits, and once that happens, the entire inference pipeline degrades. Unlike CPU systems where thermal throttling is rare, GPU thermal management is an active operational concern.

Teams need to monitor GPU temperature, understand how utilization affects thermal conditions, and make architectural decisions (fewer simultaneous requests, striping load across more GPUs) to prevent thermal throttling.

Getting this wrong means that as load approaches what the infrastructure should theoretically handle, performance collapses instead of scaling gracefully.

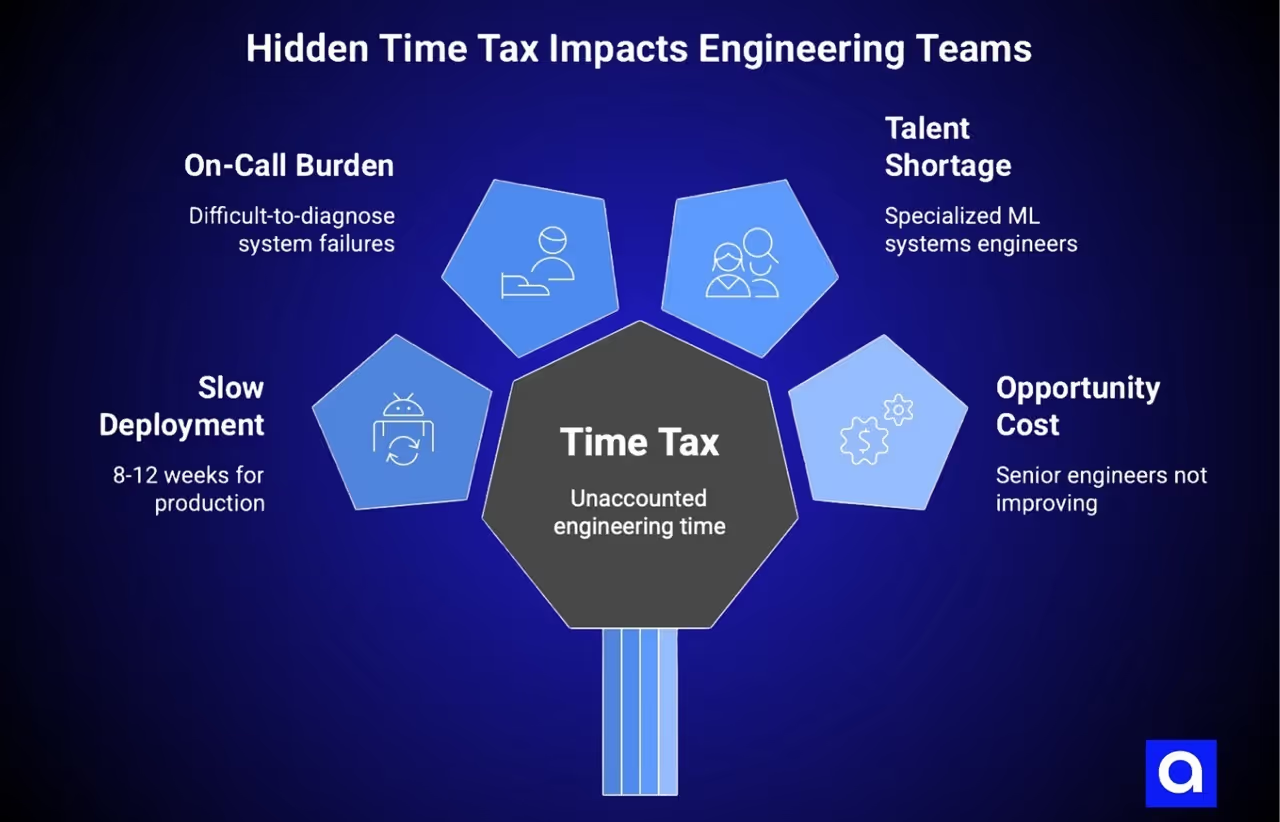

What’s The Hidden Time Tax on Engineering Teams?

Beyond the technical challenges, there's a significant hidden cost in engineering time and organizational focus that most teams don't account for in initial planning. This time tax manifests across several dimensions.

The initial learning and ramp-up period for deploying open-weight models is substantial. A team without prior experience running inference workloads typically needs 8-12 weeks before they have a production-ready deployment. This isn't linear. A team will spend 3-4 weeks getting a model running in test, think they're ready for production, run into an unforeseen issue at week 5, spend 2 weeks debugging the CUDA version incompatibility, then discover at week 8 that their storage architecture doesn't meet latency requirements. The end result is a production deployment, but the calendar time far exceeds what experienced teams would require.

Once in production, open-weight models become a significant on-call and maintenance burden. Model serving systems fail in ways that are difficult to diagnose and predict. You might have a cascade failure where one model's GPU memory corruption destabilizes the GPU for other models being served on the same hardware. You might have inference requests that touch unexpected code paths and cause the model or inference framework to consume far more memory than expected. You might have requests with unusual prompt lengths that expose bugs in the inference framework that only manifest under specific conditions. Each of these scenarios requires someone with both infrastructure knowledge and ML systems knowledge to debug and resolve. For many organizations, this creates a painful staffing situation where the senior engineers who understand enough to debug these issues end up on-call for production inference, which becomes a significant quality-of-life issue and a retention risk.

The talent market for ML systems engineers is remarkably tight, and acquiring this expertise internally is extremely challenging for most teams. ML systems engineering is still a relatively specialized field. There simply aren't that many people with years of production inference experience. The people who have this experience tend to work at large tech companies or startups specifically focused on AI infrastructure. Recruiting someone with this expertise to join a traditional company's infrastructure team is difficult and expensive. Training someone from a traditional DevOps background to become an ML systems engineer is possible but takes 12-24 months and requires significant mentorship. Many teams that successfully deploy open-weight models find themselves unable to scale further because they can't hire the people needed to expand the program. This creates a bottleneck that shows up as a business limitation. You can run one or two models in production, but you can't scale to many models because the team that maintains them is fully saturated.

There's also the opportunity cost consideration. When your senior platform engineers are spending 30% of their time troubleshooting GPU driver issues and optimizing inference memory management, they're not available to work on other infrastructure improvements that might have broader organizational impact. They're not improving CI/CD pipelines, enhancing observability, or working on other platform initiatives that could benefit many teams. The organizational drag from concentrating expertise on a single challenging domain can be substantial, especially in smaller organizations where the pool of senior engineers is limited.

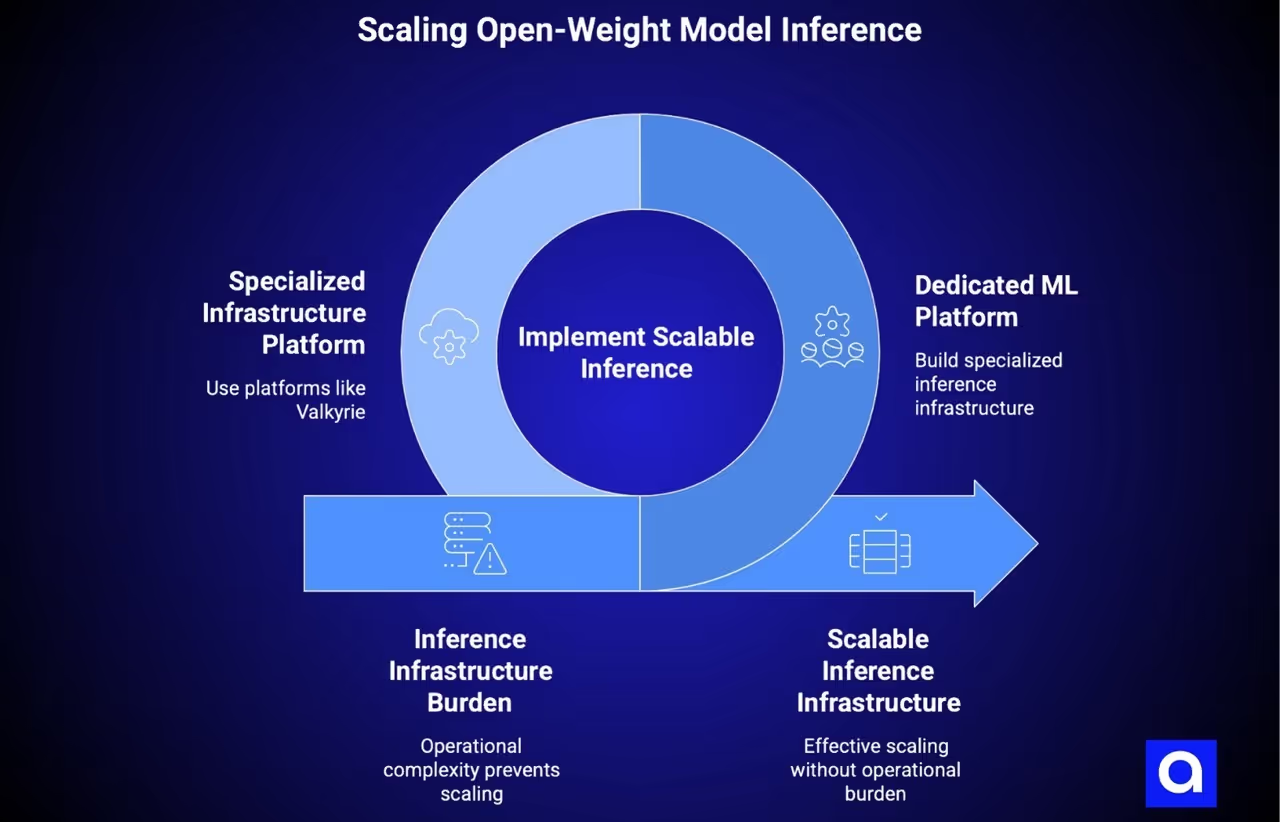

What Successful Teams Do Differently While Deploying Open-Weight Models?

Teams that have successfully run open-weight models at scale consistently fall into one of two categories: those that have built dedicated machine learning platform teams, and those that use specialized infrastructure platforms designed specifically for this workload.

The first category, organizations with dedicated ML platform teams, typically allocate 4-6 engineers specifically to building and maintaining inference infrastructure. These engineers have backgrounds in machine learning systems, GPU optimization, and distributed systems.

They're not borrowed from the general DevOps pool; they're hired specifically for this expertise. The ML platform team owns everything from model packaging and optimization to inference service deployment to GPU resource management. This organizational structure works because it creates a clear separation of concerns.

The ML platform team becomes the specialized center of excellence for inference infrastructure, while other teams consume their services. Companies like Anthropic and OpenAI have built organizational structures along these lines. For most organizations, this structure is not realistic, both because the talent is difficult to recruit and because the investment in a 4-6 person specialized team is only justified if you're running inference at massive scale.

The second category, organizations that use specialized platforms like Valkyrie, sidesteps the need to build this expertise internally. These platforms abstract away most of the GPU-specific operational complexity, provide multi-cloud GPU brokering so you're not locked into a single provider or constrained by a single region's availability, and handle the optimization decisions that would otherwise require deep ML systems expertise.

A team using such a platform still needs to understand inference concepts like batching and quantization, but they don't need to understand CUDA driver versioning, memory fragmentation strategies, or GPU thermal management. They can focus on the application-level concerns: building the integration with their systems, instrumenting observability, making optimization decisions about model selection and quantization.

Platforms like Valkyrie let teams get the benefits of open-weight models without the operational burden that typically prevents most organizations from scaling inference infrastructure effectively.

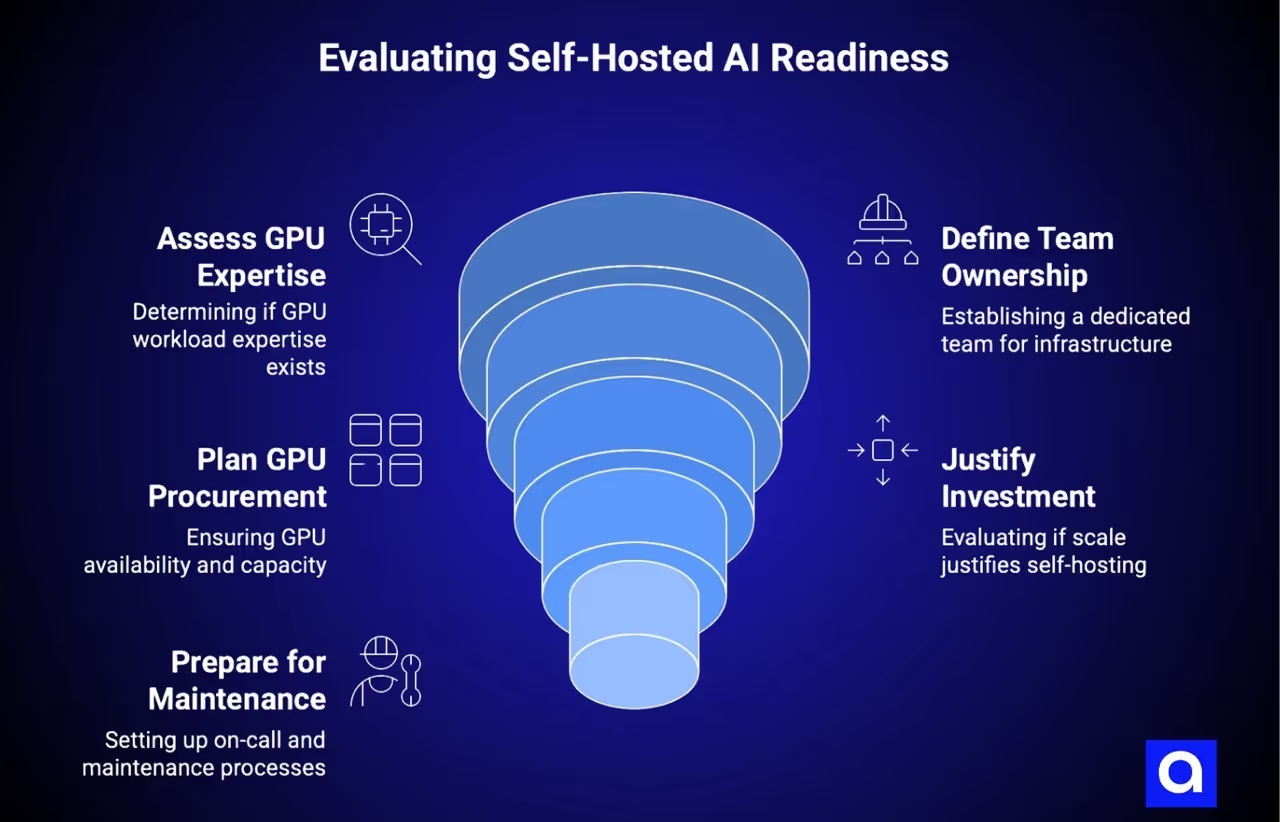

How to Evaluate Self-Hosted AI Readiness? Questions to Ask Before Deployment

Before committing to self-hosting open-weight models, honestly assess whether you have the prerequisites in place. Several key questions can guide this evaluation.

First, does the organization have existing expertise in GPU workloads? If the answer is no, then you're not just deploying an open-weight model, you're simultaneously building the expertise to manage it. This is possible, but it requires realistic timelines and expectations. Adding 8-12 weeks to your deployment timeline to account for the learning curve, or allocating 1.5 FTE of senior engineer time, is the realistic cost of acquiring this expertise.

Second, is there a dedicated team that will own this infrastructure long-term, or is this being added to a general DevOps team's existing responsibilities? If it's the latter, be very clear about what other work is being deprioritized. Inference infrastructure doesn't work well as "the thing we do in our spare time." It requires continuous attention and dedicated focus.

Third, do you have the GPU procurement and capacity planning processes in place? Have you actually talked to cloud providers about GPU availability, or are you assuming you can just spin up instances? Have you validated that the GPU types you're planning to use are available in the regions where you need them? GPU availability is increasingly the bottleneck in deployment planning, and waiting 8 weeks to discover that H100s aren't available in your desired region is painful.

Fourth, does your organization have the scale to justify the investment? If you're running inference serving a few hundred requests per day, the operational complexity of managing your own infrastructure might not be worth it compared to using an API. The breakeven point for self-hosting depends on your specific workloads and costs, but it's typically somewhere in the range of billions of tokens per month.

Finally, are you prepared for the on-call and maintenance burden this will create? Who will be responsible for 2 AM production incidents with GPU driver crashes? Do you have the capacity for that person to be pulled off other work when it happens? Is your organization comfortable with that arrangement, or do you need to hire additional capacity?

Choosing Your Path: Self-Hosting vs. Managed AI Infrastructure Platforms

Open-weight models represent a genuine opportunity for organizations that want to deploy advanced AI capabilities without vendor lock-in or per-token pricing constraints. But realizing this opportunity requires a clear-eyed assessment of the operational challenges and a realistic investment in either building internal expertise or using specialized platforms that abstract away much of the complexity.

Teams that rush into self-hosting without addressing the skills gap, infrastructure requirements, and operational complexity will find themselves spending far more time and money than expected, and potentially facing outcomes that don't justify the effort.

For organizations that have made the realistic assessment that they can support a dedicated ML infrastructure team, self-hosting is viable and can make sense at scale. For organizations that don't have that capacity but still want to run open-weight models, the middle ground of using a specialized inference platform offers the benefits of openness and control with far less operational burden.

Either path is legitimate, but the path that makes sense for any given organization depends entirely on where you are in your infrastructure maturity and what capacity you can realistically allocate to this domain.

Not sure which path is right for your organization? Azumo helps companies evaluate their AI infrastructure readiness and choose the deployment strategy that matches their capabilities and business goals. Whether you need help building an internal ML platform team or want to explore managed infrastructure solutions like Valkyrie, our AI experts can guide you through the decision.

Schedule a free AI infrastructure consultation to assess your team's readiness and map out the right deployment path for your open weight models.

.avif)