When the first generation of truly powerful open-weight models became available, a narrative quickly took hold in engineering organizations: self-hosting LLMs instead of paying per-token to an API provider would save enormous amounts of money.

The math seemed straightforward. An API call to a model hosted by a provider might cost $0.02 per 1000 tokens. If you're processing millions of tokens per day, that's thousands or tens of thousands of dollars per month. If you rent a GPU for $3 per hour and run requests on it yourself, the per-token cost drops dramatically. The cost of the GPU amortized across requests seems trivial compared to API pricing.

Why would you ever use an API when you can self-host?

This logic has seduced hundreds of engineering organizations into committing to self-hosted AI models infrastructure. Many of them have been surprised, sometimes pleasantly but often painfully, to discover that the actual cost of self-hosting is dramatically higher than the simple arithmetic suggested.

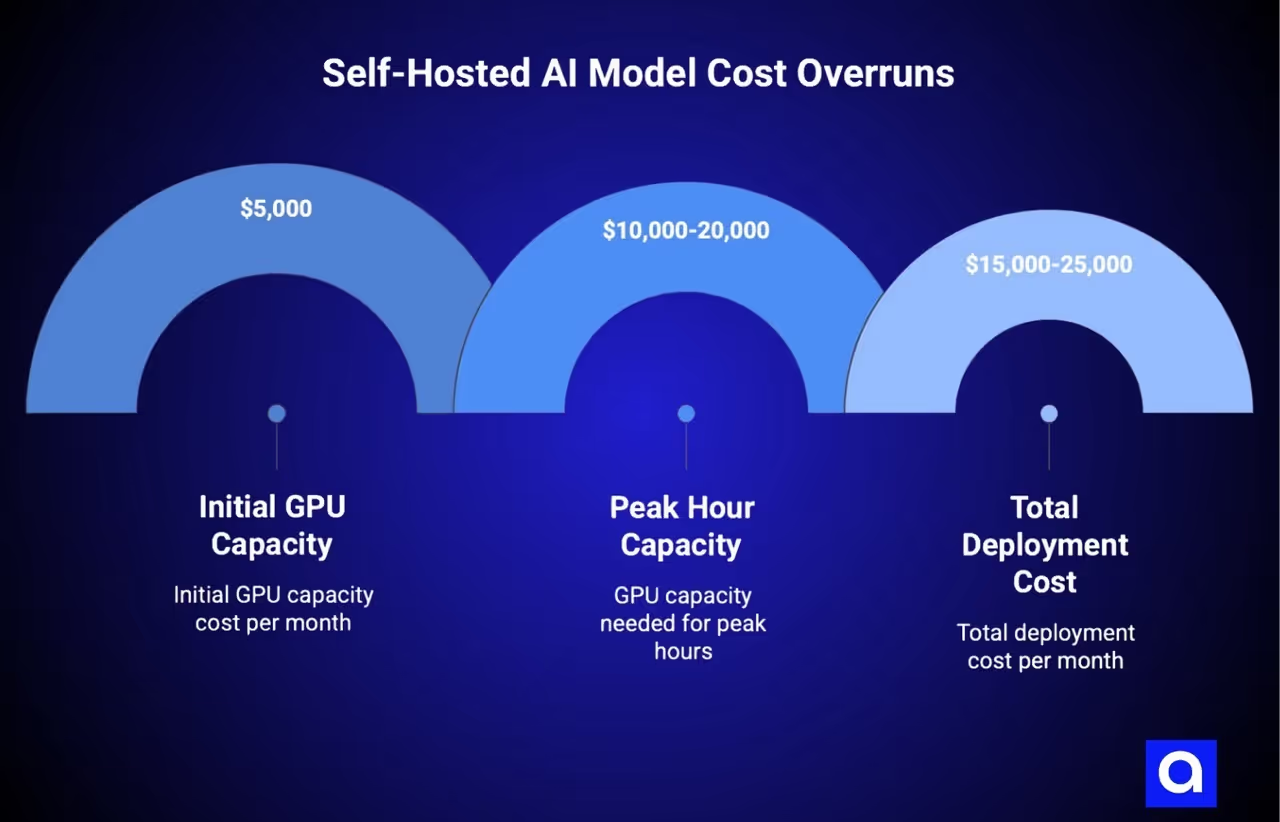

The hidden costs are not marginal. They're often larger than the cost of the GPU infrastructure itself. A team that expected to spend $5,000 per month on GPU infrastructure ends up spending $25,000 per month when you account for engineering time, infrastructure complexity, sub-optimal utilization rates, and opportunity costs.

Some of these costs are direct and obvious once you look for them. Many are indirect and distributed across the organization in ways that make them easy to miss until months or years have passed.

Understanding the true self-hosting LLM cost structure is essential for making rational decisions about infrastructure. This isn't an argument that self-hosting is always wrong. At sufficient scale, self-hosting makes strong economic sense.

But for the large middle band of organizations processing billions of tokens per month but not hundreds of billions, the economics are far less clear than the simple per-token calculation would suggest. Many of these organizations would be better served by solutions that capture most of the benefits of self-hosting while reducing the hidden cost burden.

What’s The Real Cost Structure of Self-Hosting LLMs? Beyond GPU Pricing

When most teams evaluate whether to self-host an open-weight model, they account for GPU costs and maybe some vague notion of "operations overhead." They don't build a comprehensive cost model that captures all the actual expenses. A realistic cost structure for self-hosted inference includes far more categories than most teams initially consider.

The first and usually largest hidden cost is engineering time. Deploying and maintaining a self-hosted AI models in production requires more engineering effort than most teams anticipate.

In our work with clients, we've observed that the initial deployment phase typically requires 2-4 full-time engineers for 3-6 months. This isn't something you can accomplish with partial allocation. If you try to deploy inference as a 20% project for engineers who are mostly working on other things, the timeline stretches to 12+ months and the quality of the work suffers.

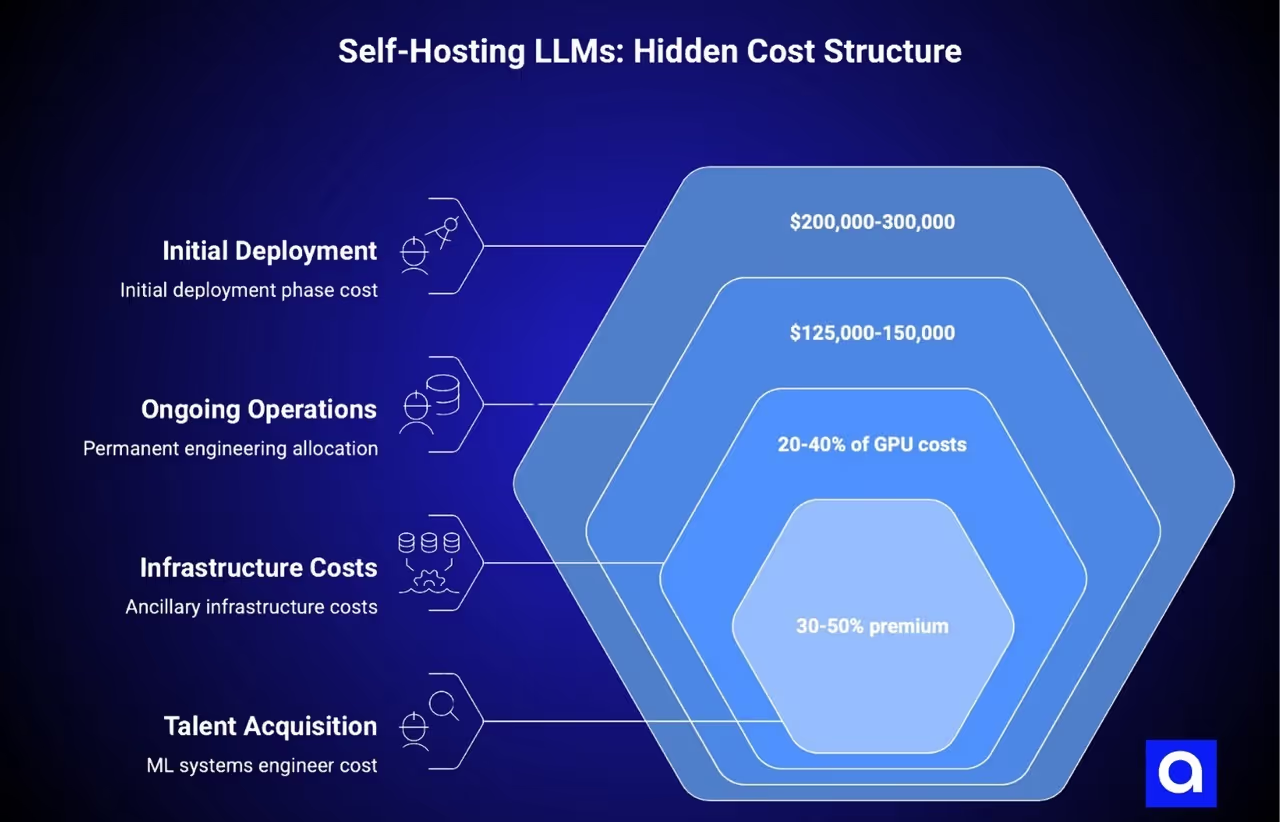

A realistic allocation is 2 engineers dedicated full-time to the project for 4-5 months. At a loaded cost of $250,000 per FTE per year (which is typical for engineering salaries plus overhead in major tech markets), this is a $200,000-300,000 cost for the initial deployment phase.

This cost often isn't captured in the infrastructure budget. It comes out of the engineering org's planning and allocation, which makes it easy to miss when you're calculating whether self-hosting saves money.

Once initial deployment is complete, there's an ongoing operational cost that teams consistently underestimate. Inference infrastructure doesn't operate on a fire-and-forget principle like many other systems. It requires continuous monitoring, optimization, and maintenance.

A production inference fleet supporting serious workloads typically requires a dedicated on-call rotation from 1-2 engineers. This means you're consuming roughly 25-50% of one engineer's time indefinitely in an on-call context, even if they're not responding to alerts every single day. That's another $125,000-150,000 per year in permanent engineering allocation.

Additionally, there are optimization tasks that emerge over time as patterns in usage become clear. A model serving 10M tokens per day might have optimization opportunities that could reduce latency or increase throughput by 30-40%, which would save thousands of dollars per month.

But capturing that requires an engineer to analyze performance patterns, identify optimization opportunities, implement changes, and validate results. This work often doesn't get done because the on-call engineer is too busy putting out fires, but the opportunity cost is real.

The infrastructure cost beyond just GPU hardware is also significant and often underestimated. A single GPU doesn't get you production inference. You need load balancers to distribute traffic across multiple inference instances. You need persistent storage for model weights that can handle the I/O demands of loading large models. You need networking infrastructure that can handle the bandwidth demands of distributed inference. You need monitoring and observability infrastructure that goes significantly deeper than typical application monitoring. You need GPU-level telemetry, memory profiling, and thermal monitoring. You need secrets management, configuration management, and deployment orchestration that's more complex than standard Kubernetes deployments because of the GPU-specific requirements.

All of this infrastructure adds cost beyond the GPU instances themselves, and it requires either purchasing additional managed services or allocating engineering time to build these capabilities in-house. In cloud environments, these ancillary infrastructure costs often add 20-40% to the GPU costs. In on-premises environments, the costs are even higher when you account for the power, cooling, and network infrastructure needed to support a GPU cluster.

Talent acquisition and retention costs create another dimension of significant hidden expenses.

Teams that successfully run open-weight models often need to hire or retain people with specialized ML systems expertise. These people are expensive, substantially more expensive than conventional DevOps engineers.

In major tech markets, an ML systems engineer with production experience commands a 30-50% premium over a standard senior engineer. If you need to hire one or two of these people to accelerate your deployment or build out your platform team, that's a real cost difference compared to using a service that abstracts away that requirement.

Even if you don't explicitly "hire for inference," retaining an engineer who becomes the go-to person for GPU issues and inference optimization requires a higher compensation than they might receive in a different role, or you risk losing that person to a company where they can apply their specialized expertise more broadly.

Why Self-Hosted AI Models Cost 3-5x Initial Estimates

When teams first evaluate self-hosting economics, they typically make several optimistic assumptions that don't hold up in practice. Understanding these common estimation errors helps explain why actual costs diverge so dramatically from initial projections.

The first major estimation error involves timeline assumptions. When an experienced team evaluates how long it will take to deploy an inference service, they often use their prior experience with application deployment as an anchor. "We deployed our new API service in 8 weeks" becomes "we should be able to deploy inference in 8-10 weeks."

What they're not accounting for is the difference between deploying a service that has well-established patterns and deploying a service that requires specialized expertise that doesn't exist in the organization.

The typical outcome is that initial deployment takes 12-16 weeks instead of 8 weeks. Then when production traffic arrives and edge cases emerge, there's another 4-8 week period of stabilization and optimization before the service is truly production-grade.

The total timeline becomes 4-6 months instead of 2 months. In terms of engineering cost, this 200% increase in timeline translates directly to 200% increase in deployment costs.

The second major estimation error involves capacity utilization assumptions. Teams typically estimate GPU utilization based on theoretical maximum capacity: if a GPU can handle 100 requests per second and you expect 50 requests per second on average, you assume 50% utilization.

What they don't account for is that actual utilization patterns are much more peaky than this. Requests aren't evenly distributed throughout the day. They cluster around certain times of day based on when users are active.

During peak hours, your GPU needs to handle 5-10x the average load, which means you need enough capacity for those peak loads. But that capacity sits idle during off-peak hours.

The result is that average utilization across the day is typically 20-40% instead of the 70-80% that was projected. This means you need 2-4x more GPU capacity than the naive calculation suggests.

The implications are dramatic: you thought you needed $5,000 worth of GPU capacity per month, but the actual requirement is $10,000-20,000 to handle peaks while not overloading during those peak periods.

Another critical estimation error involves the assumptions about how much optimization work will happen and how much impact it will have. Teams often assume that the inference framework they choose will work well out of the box, and that any optimization beyond the default configuration will be marginal. What they encounter in practice is that the default configuration often wastes 30-50% of available capacity.

Switching from continuous batching to static batching for certain request patterns can improve throughput by 40%. Implementing request priority queues can improve p99 latency by 50%. Changing quantization strategies can improve memory efficiency by 20%. But realizing these optimizations requires engineering work.

An engineer needs to profile the actual workload, identify what's not optimal about the current configuration, make changes, test them, and validate that the improvement is real and doesn't break anything else. This work takes weeks, and it's often not included in the initial timeline because teams assume the framework will be "good enough" out of the box.

The timeline extensions combine with optimization work requirements to create a schedule that's much longer than initially projected, which cascades into much higher engineering costs. An 8-week project that stretches to 20 weeks and requires continuous optimization efforts going forward has a very different cost profile than what was originally budgeted.

Self-Hosting LLM Cost Comparison: DIY vs. API vs. Managed Platforms

To properly evaluate the self-hosting question, we've built comprehensive cost comparisons between three approaches: API-based inference, self-hosted inference, and platform-based inference services that sit in the middle. Let's walk through what we've observed in production environments.

Consider a representative scenario: an organization processing 1 billion tokens per month of inference workload. This is meaningful volume, enough that the per-token cost matters, but it's not massive scale where the economics become obviously favorable toward self-hosting.

With an API-based approach using a provider like Anthropic or OpenAI (see our comparison of top LLMs), the direct cost at current pricing would be roughly $1,000-2,000 per month for 1B tokens, depending on the model and provider. There's no engineering cost to deploy, no infrastructure to maintain, no on-call burden. The total cost is essentially just the API fees.

With a self-hosted approach, you're looking at a much more complex cost structure. GPU costs for adequate capacity to handle peaks might be $8,000-12,000 per month (accounting for the 2-4x overprovisioning needed for peak handling). The initial deployment would consume 2 engineers for 4 months, which is $200,000 in engineering cost spread over the first four months (or $50,000 per month if amortized).

Ongoing operational costs for on-call coverage and optimization would be $12,000-15,000 per month ($1-1.25 FTE at loaded cost). Supporting infrastructure, monitoring, etc. adds another 25% to hardware costs, so $2,000-3,000 per month. The total monthly cost is $62,000-80,000 in the first few months, then $22,000-31,000 per month in ongoing costs.

To break even with the API approach, you need to be processing such large volumes that the infrastructure costs make sense, which is well above 1B tokens per month.

A platform-based approach like Valkyrie sits in the middle. These platforms typically cost 20-30% less than public cloud GPU pricing due to multi-cloud brokering and optimization, but they handle all the operational complexity and provide unified APIs that work across different cloud providers and hardware.

The cost is typically $4,000-6,000 per month for the same workload. There's minimal deployment effort, probably 2-3 weeks instead of 4 months, and you don't need specialized GPU expertise because the platform handles driver management, CUDA version compatibility, and most optimization work.

The total organizational cost is the platform fees plus maybe $5,000-10,000 in deployment costs, and you still don't have the ongoing on-call burden.

In the 1B tokens per month scenario, the API approach is cheapest if all you care about is direct out-of-pocket cost. But the constraint is that you're locked into a single provider, and you have no control over latency or data handling.

The self-hosted approach makes sense if you're processing 5-10B tokens per month or more, and you have the engineering capacity to make it work. The platform approach makes sense for most organizations in the 500M-5B token range because it captures most of the cost benefits of self-hosting while keeping the operational burden and expertise requirements manageable.

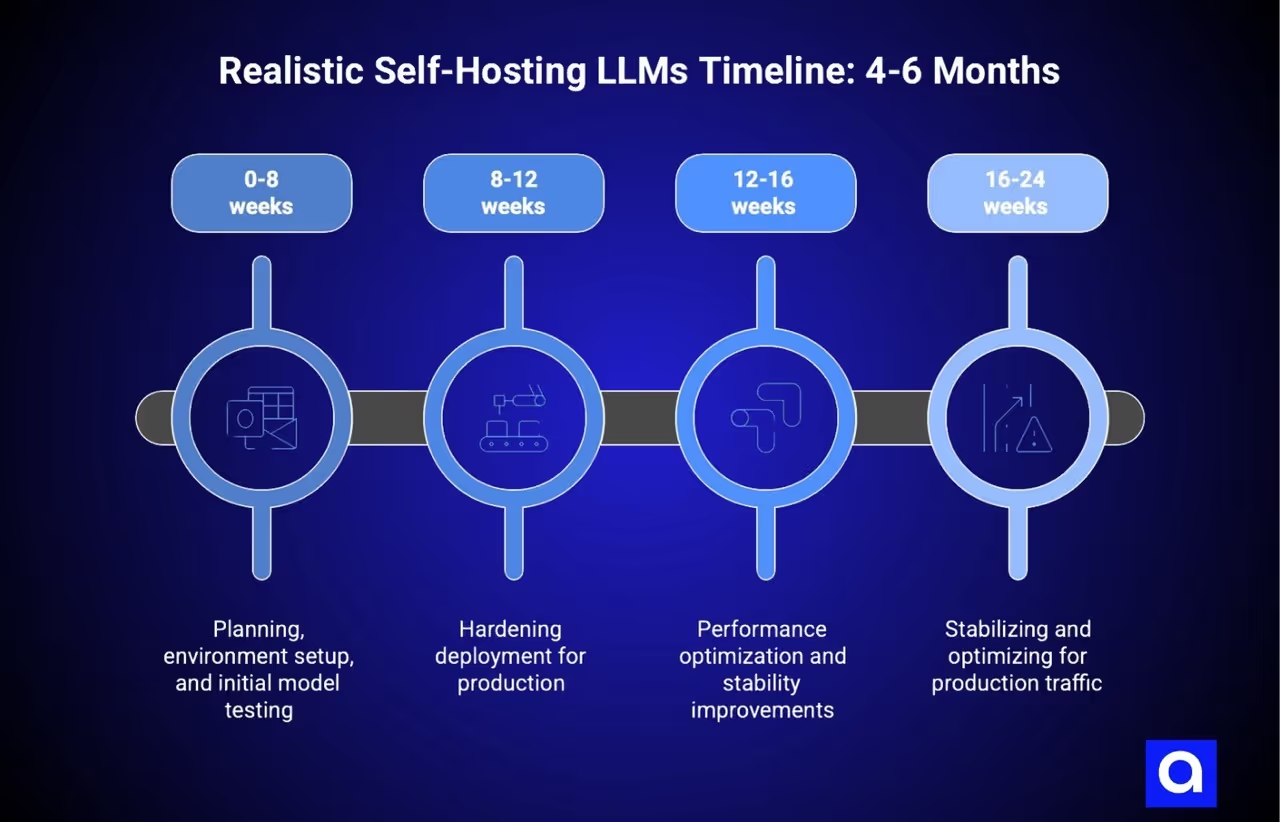

Self-Hosting LLMs Timeline: Why 4-6 Months Is Realistic

Most teams planning self-hosted AI models begin with a mental model of the timeline that's based on how long it takes to deploy conventional applications. This mental model is wrong, and correcting it is essential for accurate cost estimation.

A realistic timeline for initial production deployment of self-hosted inference is 4-6 months from planning to having a service that's ready for real traffic. This timeline assumes you already have GPU infrastructure available or can get it within 4-6 weeks. If GPU procurement is a constraint, which is increasingly common, add 6-8 weeks to the timeline.

The first 6-8 weeks are spent on planning, environment setup, and getting the first model running in a test environment. This is the part that's relatively quick and often where teams develop false confidence about their progress. "We got the model running, we're on track" they declare at week 8.

Weeks 8-12 are typically consumed by hardening the deployment for production, building observability, setting up monitoring and alerting, implementing authentication and authorization, building deployment automation, and countless other infrastructure tasks that are necessary but don't directly get you closer to running the model. Progress in this phase is slower and less visible than the test phase, which is why timelines often slip here.

Weeks 12-16 are usually consumed by performance optimization, stability improvements, and addressing the edge cases that emerge when you actually try to handle production traffic patterns. A model that worked fine in testing with controlled request patterns sometimes has unexpected behavior under real traffic.

Requests with unusual characteristics (very long prompts, specific token sequences) might expose bugs or expose performance problems that weren't apparent in testing. This phase is where you discover that the memory management strategy you chose works fine 95% of the time but fails catastrophically in the remaining 5%, or that the inference framework has a bug that only manifests under certain conditions.

Weeks 16-24 are typically the "okay, it's mostly working but we're still finding stability issues" phase. An organization might declare the service production-ready at week 16 or 18, but you'll typically still be dealing with stability issues and optimizations for another 2-3 months.

The realistic outcome is that you have something that functions as a production service around month 4, but you're still stabilizing and optimizing it through month 6. If you need to deploy a second model while you're still stabilizing the first, the timelines overlap and you end up with a team that's fully consumed by infrastructure work instead of producing value.

This is the reality that most team timelines miss: they account for the parallel execution task (deploying the first model) but don't account for the reality that deploying the second model happens while the team is still in high-touch maintenance mode with the first.

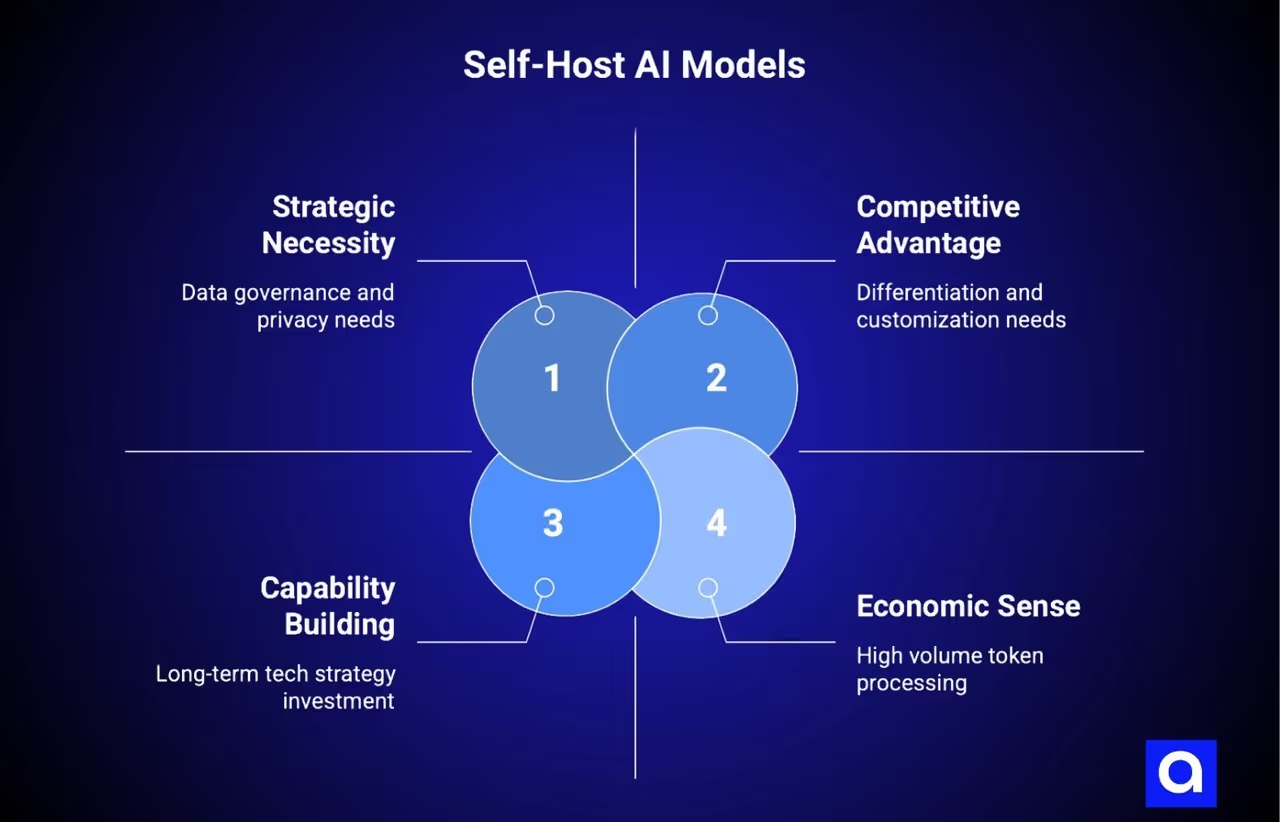

When Self-Hosting Makes Strategic Sense

There are scenarios where self-hosting open-weight models makes strong strategic and economic sense. Understanding when you're in one of these scenarios is important for making good decisions.

The first and most obvious case is scale. If you're processing 10 billion or more tokens per month, the math strongly favors self-hosting from a pure cost perspective. At that scale, the GPU infrastructure costs are amortized across enough tokens that the per-token cost drops to $0.001-0.002, which is less than most API providers charge.

But the scale threshold is higher than many teams realize. It's not 1 billion tokens. It's more like 10 billion or higher, and that's assuming good utilization and optimization. For organizations processing this volume, self-hosting should be a serious consideration.

The second case is data governance and privacy requirements. If you operate in a regulated industry (healthcare, finance, etc.) or process sensitive data that you can't send to a third-party API, self-hosting becomes strategically necessary rather than just economically advantageous.

The ability to run everything in your own infrastructure and maintain complete control over where data goes is worth significant cost overhead. If this is your situation, self-hosting might be your only option, and the question becomes "how do we make it work" rather than "should we do this?"

The third case is differentiation and customization. If running a specific model in a specific way becomes a core competitive advantage for your business, the investment in specialized infrastructure is justified. Organizations pursuing this path often need expertise in fine-tuning LLMs to maximize their competitive advantage.

If your business model fundamentally depends on being able to run custom model modifications or achieve latency characteristics that standard APIs can't provide, self-hosting might be the path to that capability. This is true for some AI-native companies, but it's not true for most organizations that are adding AI capabilities to existing products.

The fourth case is technical capability building. Some organizations view building internal expertise in running open-weight models as strategically important for their long-term technology strategy, even if it's not the economically optimal decision right now.

This is a valid strategic choice, but it should be made explicitly, with clear understanding that you're making an investment in capability that will pay off over years, not months. If you're investing in capability building, you need to acknowledge that the first 1-2 years might be more expensive than alternatives, and you need executive support for that investment.

The final case is organizational scale and existing infrastructure. If you already have a dedicated infrastructure or platform engineering team, and you already operate large-scale distributed systems, adding inference infrastructure might be incrementally cheaper for you than for organizations starting from scratch. You already have monitoring systems, deployment infrastructure, and deep expertise in operating complex systems.

The marginal cost of adding inference to what you already do might be lower than building a platform-based solution would be. This is true for large organizations but less true for smaller organizations that don't have these existing investments.

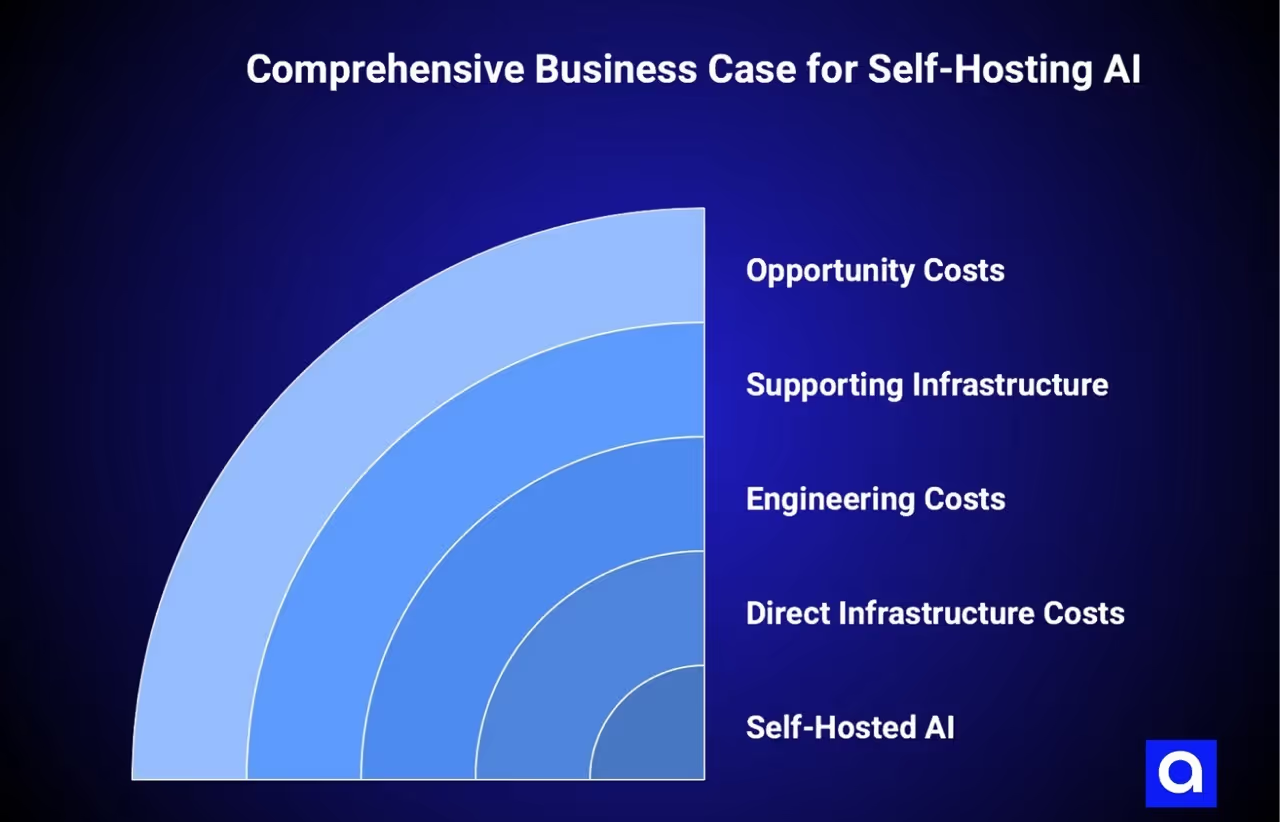

Building an Accurate Business Case

Most organizations that decide to self-host don't build a truly comprehensive business case. They typically build a case that looks something like "if we process X tokens per day at $0.05 per token with an API, that's Y cost. We can run it ourselves for a GPU that costs Z per month, which breaks even at X/2 tokens per day." This simplified analysis misses most of the real costs.

A comprehensive business case needs to include several cost categories. The first is direct infrastructure costs: GPU costs, storage costs, networking infrastructure, power and cooling if on-premises. Be realistic about utilization. Use 30-40% as your expected average utilization, not 70-80%.

The second is engineering costs: estimate the deployment timeline at 4-6 months with 2 FTE, then add ongoing operational costs at 1 FTE for on-call and optimization work.

The third is supporting infrastructure: monitoring, observability, deployment automation, configuration management, secrets management.

The fourth is opportunity costs: what would those 2 engineers have worked on if they weren't deploying inference? What would the on-call engineer be working on? Make these visible and real.

Include probability assumptions for risk scenarios. What happens if your timeline extends another 8 weeks? What happens if the first deployment runs into unexpected performance issues and requires significant optimization work? What happens if you need to deploy a second model while the first is still in high-maintenance mode?

Build these scenarios into your business case with estimated costs and probabilities. Most teams skip this step and then are surprised when actual costs exceed projections, which is exactly what a good business case should prevent.

Compare the self-hosted total cost of ownership against the API cost for 3 years, not 1 year. The first year looks bad for self-hosting because of the deployment cost. The third year looks better for self-hosting if you're at scale. See where the break-even point actually is, and whether you expect to still be running this same infrastructure at that point.

Include the exit cost if you decide self-hosting isn't working. What does it cost to move off the infrastructure you've built? Can you easily migrate to an API-based approach? Do you have lock-in around models you've optimized for your specific infrastructure?

Exit costs can be substantial and should be explicitly considered.

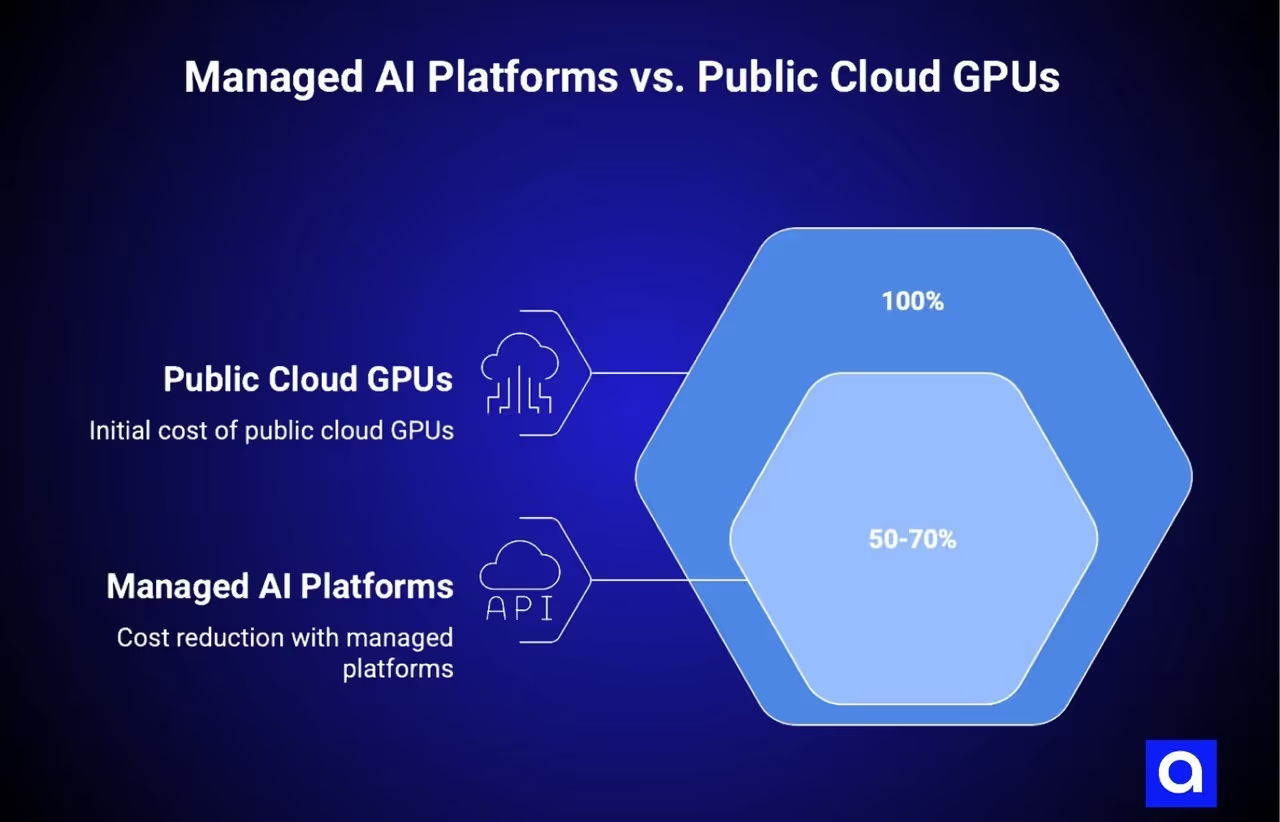

Managed AI Platforms: Reducing Self-Hosting LLM Cost by 50-70%

For most organizations, the sweet spot between cost and operational burden lies with platform solutions designed specifically for inference workloads. These platforms, like Valkyrie and similar offerings, capture many of the benefits of self-hosting while reducing the burden substantially.

We've worked with teams across industries that found this middle path aligned better with their strategic and financial constraints.

Platforms like Valkyrie abstract away most of the GPU-specific operational complexity. They handle CUDA driver versioning, CUDA compatibility validation, and framework-specific configuration. They provide unified APIs that work across multiple cloud providers, which means you're not locked into a single hyperscaler's GPU availability and pricing.

They often include multi-cloud GPU brokering that can automatically select the cheapest available GPU options, which reduces costs substantially compared to paying hyperscaler on-demand pricing. They provide built-in observability and monitoring designed specifically for inference workloads, which saves significant work compared to building custom monitoring infrastructure. They handle model packaging, versioning, and deployment in standardized ways that reduce operational complexity.

The cost of these platforms is typically 20-30% less than public cloud GPU pricing due to the multi-cloud brokering, plus a modest platform fee. The net result is usually 40-50% less cost than running the equivalent workload on public cloud hyperscaler GPUs.

Compared to the cost of self-hosting with all the engineering overhead, hidden costs, and underutilization, these platforms often end up cheaper in total cost of ownership for the 500M-10B token per month scale range.

The deployment timeline is dramatically shorter with these platforms. Instead of 4-6 months to production, you're typically looking at 2-3 weeks to get a model serving traffic.

The engineering team doesn't need deep GPU expertise because the platform handles most of the GPU-specific concerns. You still need to understand inference concepts like batching and quantization, but you don't need to understand CUDA driver versioning or memory fragmentation strategies.

The on-call burden is also reduced because the platform handles much of the operational complexity. Your team is debugging application-level issues, not GPU-level issues.

These platforms also provide better optionality than pure self-hosting. If your workload grows faster than expected, you can easily expand to larger models or increase capacity without the operational burden of managing additional GPU infrastructure.

If your workload shrinks, you can reduce capacity without being locked into a large infrastructure commitment.

If you need to move a workload between cloud providers, the platform provides unified APIs and straightforward migration paths instead of being locked into hyperscaler-specific architectures.

A platform solution represents a conscious choice to trade some of the control of pure self-hosting for a dramatic reduction in operational burden and hidden costs.

For most organizations, this is a pragmatic choice that actually delivers better outcomes than pure self-hosting.

Making Rational Infrastructure Decisions: Self-Hosted AI Models vs. Managed Solutions

The seductive simplicity of "we'll just self-host the model" logic has led many teams to underestimate the true cost of self-hosted inference. The direct cost of GPU infrastructure is often smaller than the total cost of engineering time, opportunity costs, and hidden infrastructure complexity.

For many organizations in the middle scales of inference workloads, pure self-hosting is actually more expensive than solutions that combine the benefits of open-weight models with the operational simplicity of platforms designed for this specific workload.

Making good infrastructure decisions requires building comprehensive cost models that include all the real expenses, not just the obvious ones.

It requires realistic timelines based on your actual expertise and constraints, not optimistic timelines based on deploying simpler systems. It requires a sober assessment of what opportunities you're giving up by having engineering teams focus heavily on inference infrastructure.

Most importantly, it requires recognizing that there's a spectrum of approaches between pure API dependency and pure self-hosting, and that the optimal approach for your organization probably lies somewhere in the middle rather than at either extreme.

Struggling to calculate the true cost of self-hosting LLMs for your organization? Azumo helps companies build accurate cost models that account for engineering time, infrastructure complexity, and opportunity costs, not just GPU pricing.

Whether you need help evaluating self-hosted AI models, exploring managed platforms like Valkyrie, or building a comprehensive business case, our AI experts can guide you to the most cost-effective solution.

.avif)