Walk into any large enterprise and ask where GPU infrastructure lives organizationally. The answer is usually "nobody quite knows."

Data science teams absolutely need GPUs. They're running models, conducting experiments, fine-tuning systems, evaluating architectures. These teams often also require robust data engineering infrastructure to prepare training data and manage model pipelines.

DevOps teams are supposed to provide and manage infrastructure. IT operations is responsible for compliance, security, cost management.

Yet GPUs often exist in an organizational gray zone where nobody owns them completely, everybody blames somebody else for problems, and nobody takes accountability for the entire lifecycle.

This ownership vacuum creates predictable chaos. Data science teams provision GPUs whenever they need them, often through whatever path is fastest rather than optimal. DevOps teams provide infrastructure but lack specialized knowledge to optimize for GPU workloads.

IT operations discovers unexpected cloud bills, finds unknown GPU instances running indefinitely, enforces compliance restrictions that data science teams experience as blocking. Cost explodes. Reliability suffers. Security gaps emerge. Meanwhile, enterprises waste millions on GPU infrastructure while struggling to meet workload demands.

We've observed this enterprise GPU infrastructure pattern consistently across enterprises. It warrants specific analysis. Understanding how this vacuum forms, why traditional organizational structures fail to resolve it, what successful enterprises do differently is essential for technical leaders establishing sustainable AI infrastructure.

How Enterprise GPU Infrastructure Creates Ownership Vacuums

The ownership vacuum doesn't form because organizations are poorly managed. It forms through a predictable sequence of events that feels rational at each step but creates structural ambiguity cumulatively. This sequence typically begins in data science teams.

A data scientist or ML engineer identifies a need for GPU resources, maybe training a new model or running experiments slow on CPU infrastructure. They request resources through normal channels, usually asking their immediate infrastructure provider.

In many enterprises, that request goes to cloud platforms data science teams already use. They provision GPU instances in AWS or GCP. This works well initially. The experiment completes. The GPUs are released. Nobody thinks much about ownership.

But as AI initiatives expand, data scientists increasingly need GPU resources. Requests become less one-off experiments and more persistent infrastructure needs. Some teams fine-tune models frequently. Others evaluate new architectures regularly. The one-off provisioning model stops working.

At this point, responsibility becomes ambiguous. Data science teams could manage GPU provisioning themselves, but they lack deep cloud infrastructure expertise. DevOps could take on GPU provisioning, but GPUs have specialized requirements differing from traditional infrastructure.

Different cloud regions have different GPU availability. Performance characteristics vary significantly between GPU models. Configuration involves unfamiliar concepts like CUDA versions and tensor cores. IT operations could establish GPU policies and cost management, but they lack data science expertise understanding what's actually needed.

So in most enterprises, nobody takes clear ownership. Data science continues provisioning as needed. DevOps provides some oversight but struggles with GPU-specific optimization decisions.

IT operations tries managing costs but lacks visibility into why GPUs are needed. This distributed quasi-ownership works until traffic increases and workloads become more complex. Then the vacuum creates crises.

We've observed the ambiguity compound through a second failure pattern: isolated GPU initiatives. Different business units or data science teams provision their own GPU resources.

A marketing team needs GPUs for one project. An analytics team needs different resources. Finance needs GPU compute for risk modeling. Each team provisions independently.

Each has its own cloud provider relationships, billing arrangements, operational procedures. Consolidating scattered GPU infrastructure is theoretically possible but practically challenging because nobody owns the consolidated view.

We've observed the first symptom of ownership ambiguity that most enterprises notice: financial chaos. GPU infrastructure costs accumulate in unexpected ways. Data science teams are conservative about shutting down GPU instances because they're uncertain whether they're still needed.

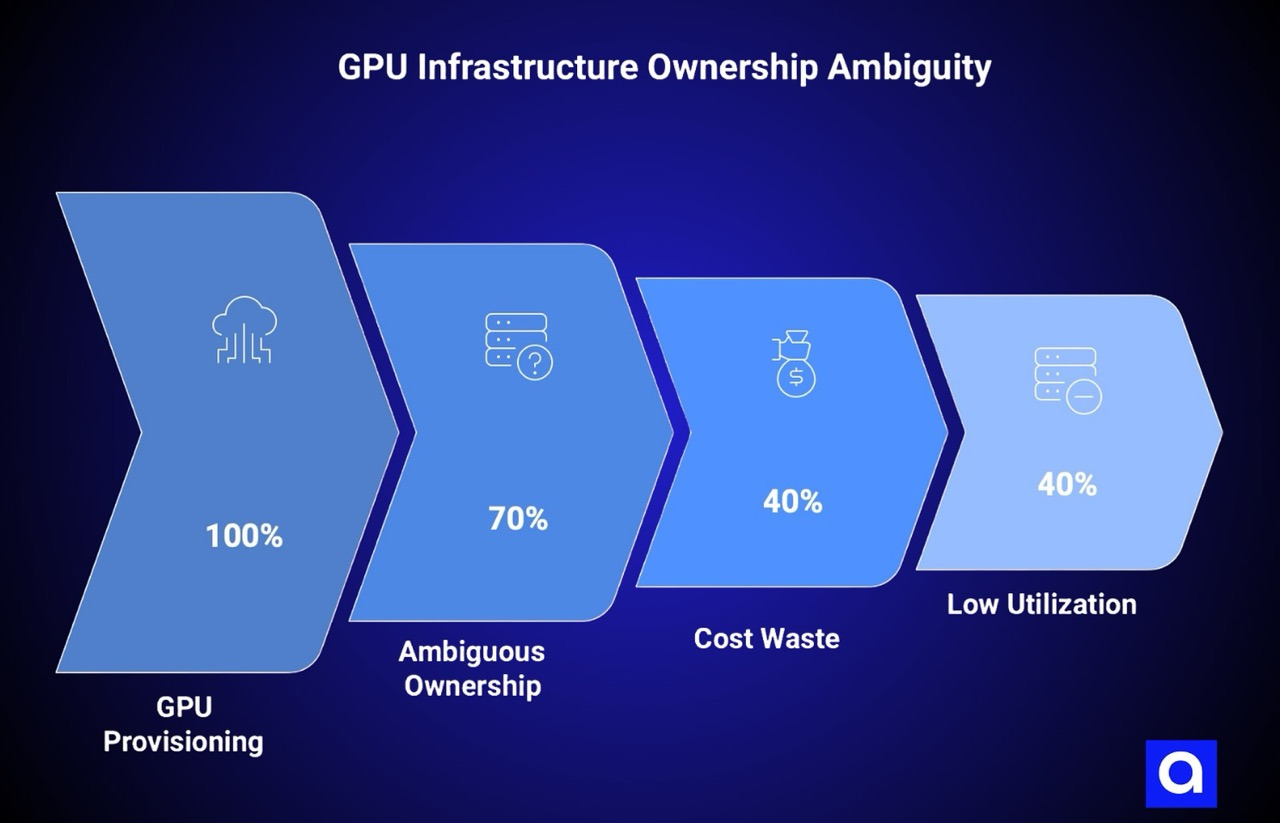

DevOps isn't tracking cost implications because GPU billing doesn't fit neatly into traditional infrastructure cost categories. IT operations discovers large GPU-related charges but lacks context for whether they're reasonable. The result: enterprises regularly spend 20 to 40 percent more on GPU infrastructure than their actual workloads require, with additional cost being pure waste.

This cost waste reflects deeper problems with utilization. When nobody owns GPU infrastructure, nobody optimizes for utilization. GPUs that could handle multiple concurrent workloads are reserved by single teams. Batch jobs run at inefficient times.

Idle GPU instances persist because nobody wants to be responsible for shutting them down and discovering later they were needed. Expensive GPU models are used for workloads that would run perfectly well on cheaper alternatives. Reserved capacity sits underutilized because provisioning was conservative and actual demand didn't materialize.

We've observed utilization problems are often worse than financial visibility suggests. In enterprises with clear GPU infrastructure ownership, utilization rates commonly reach 70 to 85 percent. In enterprises with ownership ambiguity, utilization often drops to 40 to 50 percent.

This gap represents thousands or tens of thousands of dollars in wasted monthly spend, but it's rarely visible as a single line item. The cost is distributed across cloud bills, internal allocations, chargeback systems that don't clearly expose the waste.

Cost control eventually forces action, but the action often comes too late and too heavy-handed. An executive reviews cloud spend and discovers unexpected GPU costs. They mandate reductions without understanding which workloads actually need GPUs. IT operations begins restricting GPU access, which frustrates data science teams and slows critical initiatives.

These restrictions prove unpopular enough that they're eventually relaxed without implementing better governance structures. The organization ends up back where it started: uncontrolled spending, no clear ownership, organizational friction between teams.

GPU Management Failures: Reliability And Security Gaps

Financial waste, while serious, is often not the highest-impact consequence of GPU ownership ambiguity. More serious problems emerge in reliability and security. When nobody owns GPU infrastructure, nobody takes responsibility for ensuring it's reliable.

If a GPU instance fails, the responsible team discovers it through their own monitoring, if they monitor at all. Some teams discover GPU failures only when a job supposed to complete doesn't finish. Critical model serving infrastructure might lack redundancy that would be standard for traditional application services because nobody established GPU SLOs.

Security gaps follow a similar pattern. GPU instances are often provisioned with minimal security constraints because the provisioning path emphasizes speed over security. Access controls might not be properly configured.

GPU instances might have public internet access when they shouldn't. Data science teams might be running workloads from untrusted sources without appropriate sandboxing. IT operations tries enforcing security policies, but without understanding GPU-specific risks and without organizational structures holding teams accountable, these policies often go unenforced.

The knowledge concentration problem creates additional security risk. When GPU infrastructure lives in organizational gray zones, knowledge about that infrastructure concentrates in individuals rather than documented processes. A specific data scientist knows where most GPU instances are and roughly what they do.

But if that person leaves, the knowledge walks out with them. New instances appear that nobody remembers creating. Instances from terminated projects continue running indefinitely. This knowledge concentration also creates a truck-factor problem: critical infrastructure depends on individuals lacking formal responsibility for maintaining it.

Cost overruns and utilization waste might be financial problems, but reliability and security gaps translate directly into operational risk and potential breach exposure.

Enterprises often tolerate financial waste longer than they should tolerate security gaps. When security problems emerge, the urgency of establishing clear GPU ownership suddenly increases.

Why Traditional DevOps Can't Handle Enterprise GPU Management

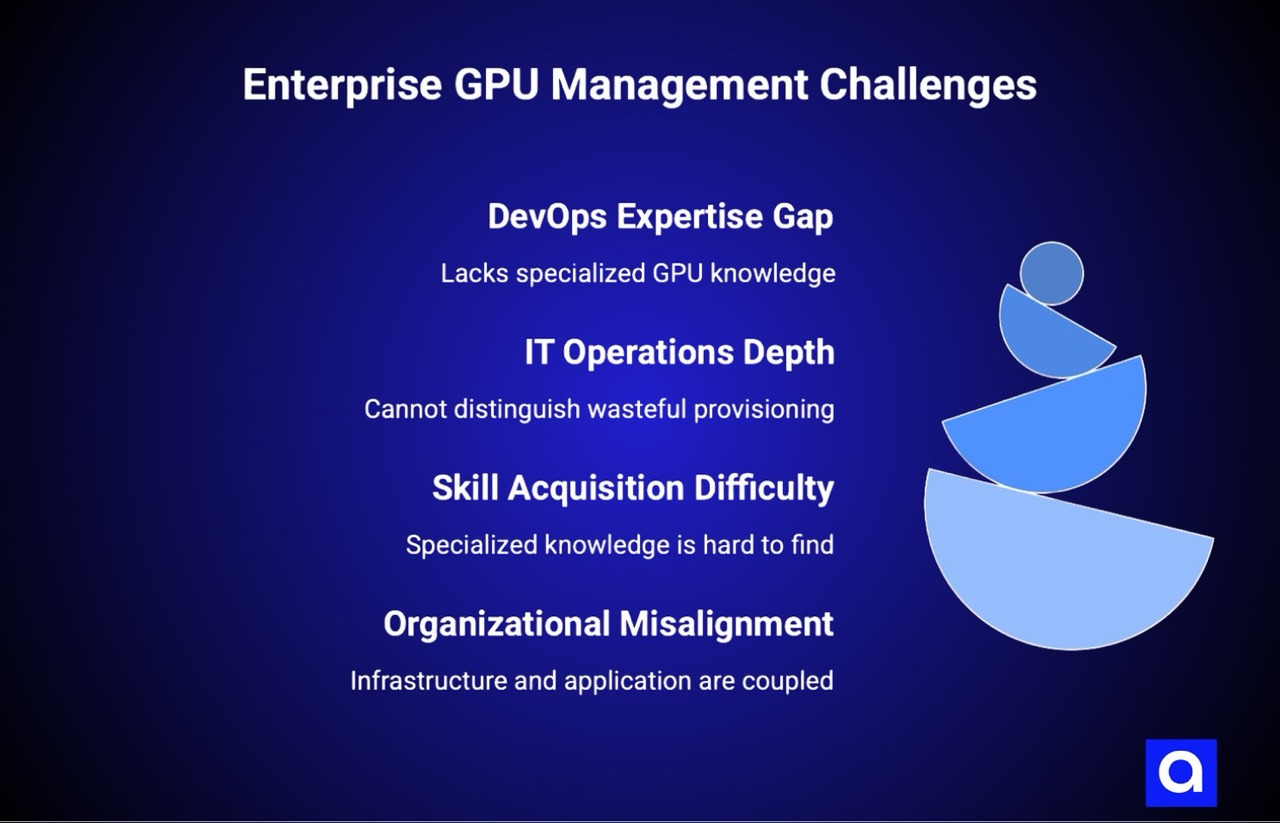

Understanding why enterprise GPU ownership ambiguity persists requires examining how traditional enterprise structures approach infrastructure. Most enterprises have evolved infrastructure organizations built around application services. DevOps manages servers, databases, load balancers, networking infrastructure. While mature cloud and DevOps practices provide a foundation, GPU infrastructure requires fundamentally different expertise and operational models.

This model works well for traditional infrastructure because these components fit naturally into teams' expertise and responsibilities. A DevOps engineer understands provisioning servers, configuring networks, managing databases. These skills are general enough to apply across many workloads.

GPU infrastructure doesn't fit this model smoothly. GPUs have specialized requirements. They need specific cloud instances with specific hardware. They need specialized software stacks—CUDA toolkits, specific PyTorch or TensorFlow versions, specialized container images. They have performance characteristics fundamentally different from CPU infrastructure.

A DevOps engineer with deep Kubernetes expertise might have no idea how to optimize GPU utilization for machine learning workloads. They might not understand the difference between different GPU models or why certain configurations perform better for specific workload types.

This expertise gap creates friction. Data science teams need infrastructure but need it configured in ways that DevOps struggles to understand or optimize. DevOps provides infrastructure but doesn't understand workload characteristics well enough to provision it efficiently.

The teams end up operating at cross-purposes. Data science wants flexibility and rapid provisioning. DevOps wants consistency and standardization. Neither organization is wrong, but the mismatch creates organizational friction that often results in neither party owning GPU infrastructure clearly.

IT operations faces a parallel problem. IT organizations traditionally own cost management, compliance, security. They're skilled at enforcing policies and tracking spend.

But GPU infrastructure requires technical depth. A cost control policy making sense for general cloud infrastructure might be counterproductive for GPU workloads. Preventing data science teams from launching GPU instances might seem like cost control, but if those instances are necessary for critical business workloads, the "savings" are actually a drag on business outcomes.

Without technical depth, IT operations can't distinguish between wasteful GPU provisioning and necessary infrastructure needs.

The skill gap problem extends beyond individual contributors. GPU infrastructure requires specialized knowledge genuinely difficult to acquire. Understanding GPU memory management, CUDA programming, tensor computation optimization, machine learning frameworks requires background different from traditional systems operations.

Finding infrastructure engineers with this background is challenging. Organizations often find it easier to defer GPU infrastructure decisions to data science teams, even though data science teams lack infrastructure expertise. This deference contributes to the ownership vacuum.

Organizational structures that worked for traditional infrastructure fail for GPU infrastructure because they assume infrastructure expertise is orthogonal to application expertise. In reality, GPU infrastructure and machine learning application expertise are tightly coupled.

We can't optimize GPU infrastructure without understanding the workloads we're optimizing for. We can't deploy machine learning models efficiently without understanding GPU characteristics. Traditional organizational separation between infrastructure and application teams creates misalignment when workloads have such tight coupling between infrastructure and application concerns.

GPU Management Models: ML Platform Teams for Enterprise GPU

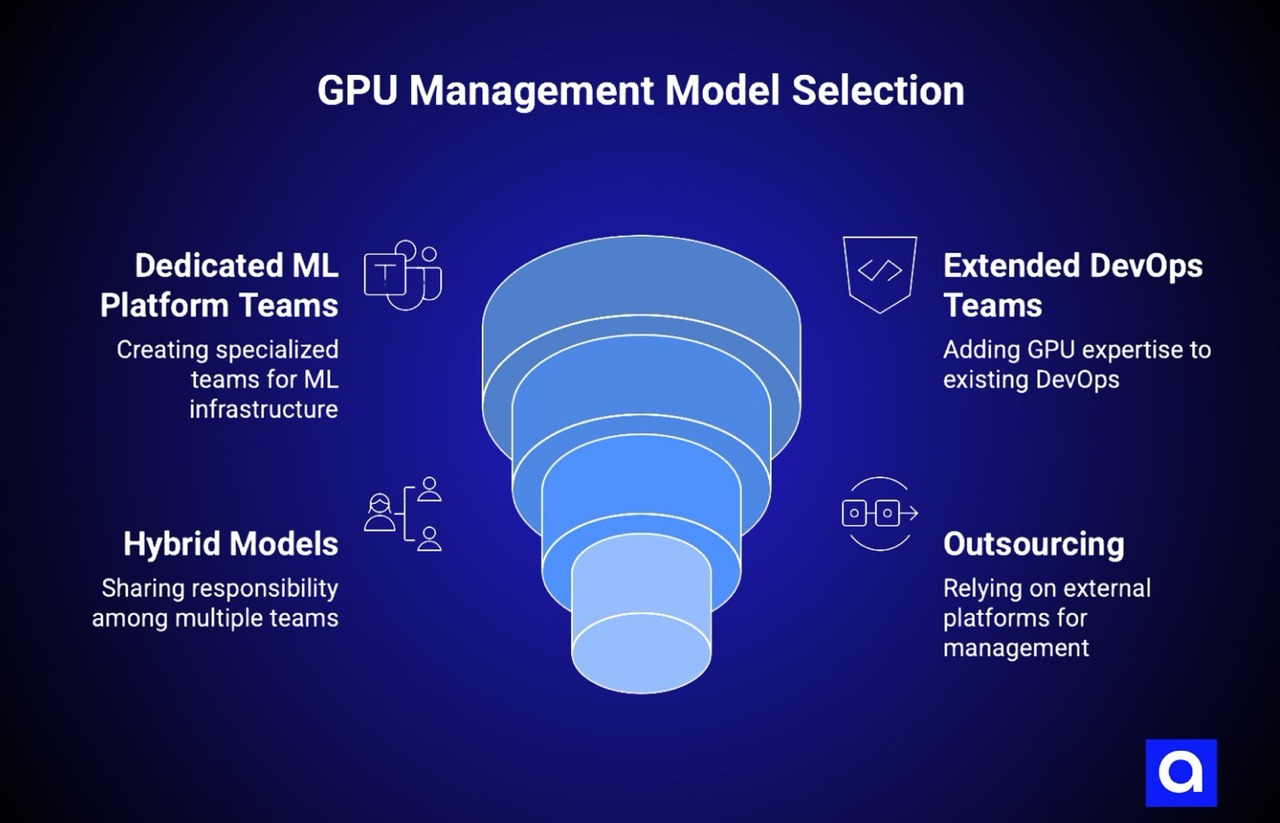

Organizations that successfully implement enterprise GPU management typically establish clear ownership through one of several models. The most common is creating dedicated ML platform teams.

These teams sit organizationally between data science and infrastructure. They understand both machine learning requirements and infrastructure management. They own enterprise GPU infrastructure provisioning, optimization, operations.

Data science teams request resources through standardized processes, and the platform team provisions and manages those resources.

This model works well because it aligns organizational structure with technical coupling. GPU infrastructure and machine learning workloads are inherently coupled, and creating teams that own both avoids the friction of trying to manage them separately.

ML platform teams can optimize infrastructure for machine learning characteristics. They understand why a particular GPU model makes sense for a workload. Successful teams also implement comprehensive MLOps platforms to manage the full model lifecycle beyond just GPU provisioning. They can consolidate infrastructure across multiple data science teams to improve utilization. They can implement sophisticated batch scheduling and resource sharing that would be difficult for traditional DevOps teams without machine learning expertise.

Successful ML platform teams typically operate with clear responsibilities and mandates. They own SLOs for GPU infrastructure, cost per inference, training throughput, metrics that matter for machine learning workloads. They charge-back GPU costs to consumer teams, creating incentives for efficient usage.

They implement self-service tools that let data science teams request resources without manual approvals while maintaining visibility and cost controls. They maintain documentation and best practices that codify infrastructure decisions, preventing knowledge concentration in individuals.

The investment in creating ML platform teams is substantial. These teams need engineers with unusual skill combinations: strong infrastructure expertise, deep understanding of GPU characteristics, sufficient machine learning knowledge understanding workload requirements. Recruiting such engineers is competitive and expensive. But the investment typically pays for itself through improved utilization, cost efficiency, faster time-to-productivity for data science teams.

A second approach is extending traditional DevOps organizations to include GPU infrastructure, with specific engineers developing deep GPU expertise. Rather than creating a separate ML platform team, organizations add GPU-specialized engineers to existing DevOps teams.

These engineers develop the expertise to manage GPU infrastructure, optimize for machine learning workloads, support data science teams.

This approach can work well in organizations where GPU workloads are limited or where existing DevOps teams are mature and adaptable. The advantage is avoiding organizational fragmentation—GPU infrastructure remains under DevOps ownership rather than creating parallel organizations.

The disadvantage is that it requires DevOps organizations to expand their scope and expertise significantly, and it may require recruiting people with atypical backgrounds for traditional DevOps roles.

Some organizations implement hybrid models where multiple teams share GPU infrastructure responsibility with explicitly defined boundaries. Data science teams remain responsible for their workload characteristics and performance requirements. Infrastructure teams become responsible for providing the GPU infrastructure meeting those requirements. IT operations remains responsible for cost management and compliance. Each team has clear accountabilities.

These models can work if boundaries are truly clear and communication mechanisms between teams are strong. Regular synchronization meetings, clear escalation paths, explicit documentation of responsibilities and expectations become critical.

Without these, shared responsibility models often devolve into ambiguity and friction. But when implemented well, they avoid the organizational overhead of creating entirely new teams while still establishing clear ownership.

A fourth approach is outsourcing GPU infrastructure ownership to external platforms. Rather than any internal team owning GPU infrastructure, the organization uses a platform provider handling provisioning, optimization, operations.

Platforms like Valkyrie handle GPU provisioning, multi-cloud brokering, model serving, operational monitoring. Internal data science teams interact with simple APIs rather than managing infrastructure directly. Cost management, security, compliance become the platform provider's responsibility.

This approach eliminates the need for specialized internal expertise and internal ownership structures. Data science teams get fast, reliable GPU infrastructure without needing to understand GPU provisioning details. IT organizations get cost visibility, security, compliance without needing to understand GPU-specific technical details.

The tradeoff is external dependency: the organization relies on a platform provider for critical infrastructure. But for many organizations, this dependency is acceptable, and the benefits of avoiding the complexity of establishing internal GPU infrastructure ownership justify the tradeoff.

How to Establish Clear Enterprise GPU Infrastructure Ownership?

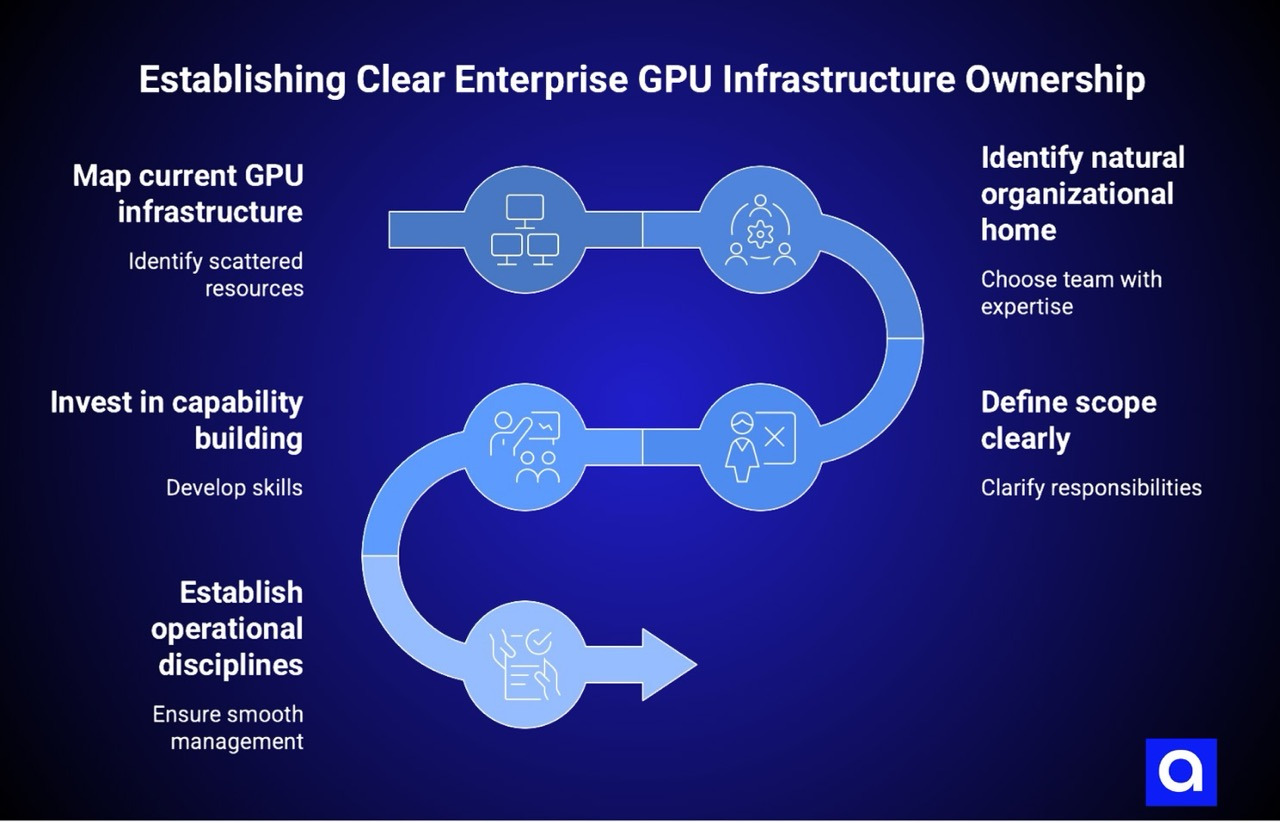

Regardless of which ownership model an organization selects, establishing clarity requires deliberate steps. The first step is mapping current GPU infrastructure. This sounds straightforward but often reveals surprising complexity. Most organizations have GPU resources scattered across multiple cloud providers, multiple projects, multiple cloud accounts.

Some are reserved instances procured months ago. Some are spot instances allocated temporarily. Some are on-premise GPU machines. Developing a complete inventory is essential. This inventory should include where each GPU lives, what it's doing, who provisioned it, how it's being used, what costs are associated.

This mapping exercise typically reveals orphaned GPU infrastructure—instances still running but no longer being used. It reveals siloed infrastructure—different teams with completely separate GPU allocations that could be consolidated. It reveals documentation gaps—instances where nobody can explain why they exist or what they do. Consolidating this information is often the hardest part of establishing clarity because it requires cooperation across multiple teams and cloud providers.

The second step is identifying the natural organizational home for GPU infrastructure. This should be the team with the strongest combination of infrastructure expertise and machine learning knowledge.

For many organizations, this is a newly created ML platform team. For others, it's extended DevOps with GPU specialists. For others, it's external platforms.

The choice depends on organizational structure, existing expertise, growth trajectory. Organizations growing rapidly with many data science teams typically benefit from dedicated platform teams. Organizations with limited GPU workloads might extend existing DevOps.

The third step is defining scope clearly. What aspects of GPU infrastructure is the responsible team owning? Are they owning the complete lifecycle from provisioning through deprovisioning? Are they owning optimization for cost and performance? Are they owning reliability and SLOs? Are they owning security and compliance?

Different scope definitions create different organizational structures and responsibilities. The important thing is explicitness—all stakeholders should understand what's included in GPU infrastructure ownership.

The fourth step is investing in capability building. Whichever team takes ownership needs the skills to manage GPU infrastructure effectively. This might require hiring new people, external training, or both. The investment timeline matters.

Organizations should plan for gradual skill building rather than expecting immediate mastery. Early mistakes in GPU infrastructure management are inevitable, and the organization should budget for learning.

The final step is establishing operational disciplines that reduce the probability of future ownership ambiguity. This includes regular inventory audits to catch undocumented infrastructure. It includes chargeback mechanisms that create cost visibility and incentives for efficient usage. It includes documentation and runbooks that codify institutional knowledge. It includes communication mechanisms that keep all stakeholders informed about GPU infrastructure status, capacity, roadmap.

These disciplines prevent the organizational forgetting that allows ownership ambiguity to reemerge.

The Strategic Cost of Poor GPU Management in Enterprise

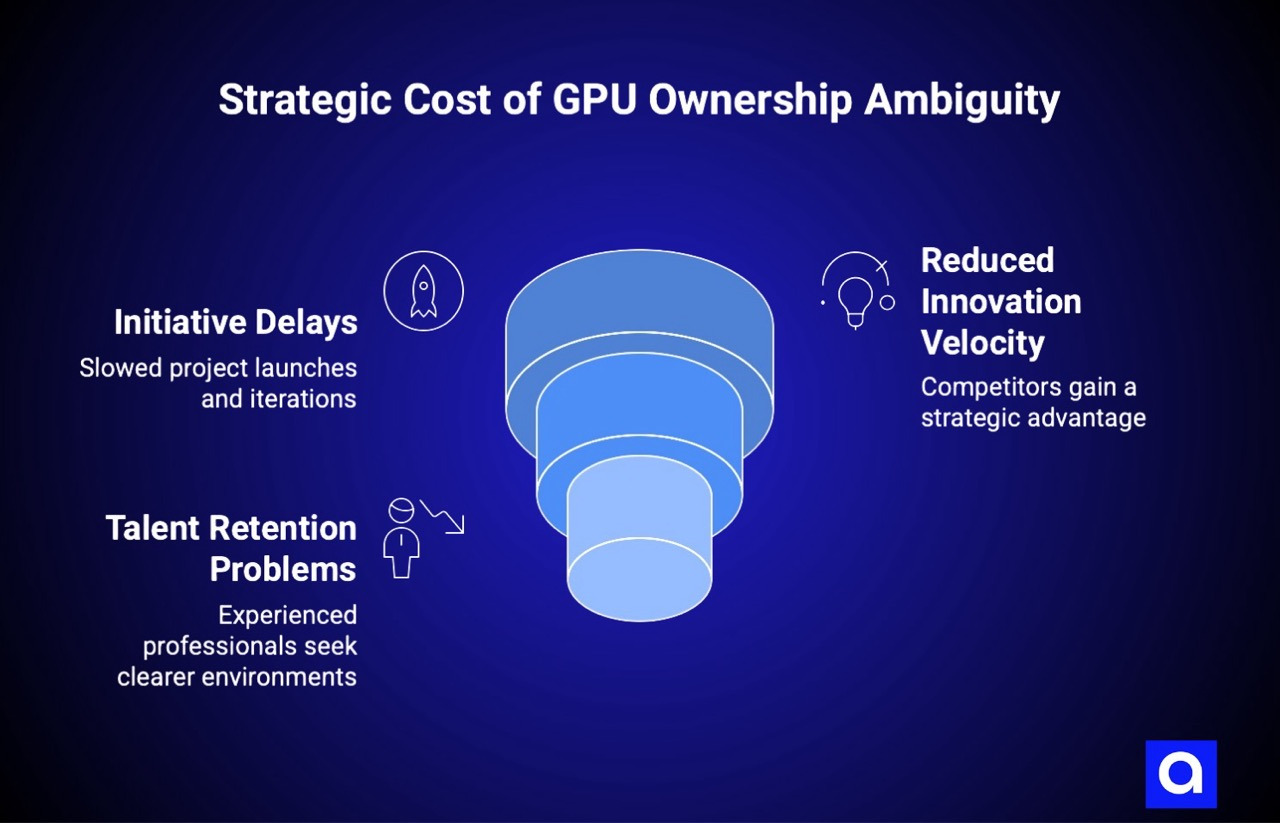

We've observed the ongoing consequences of GPU ownership ambiguity extend beyond financial waste and operational risk. They delay strategic initiatives and limit organizational agility.

When GPU infrastructure is ambiguously owned, data science teams face friction every time they need infrastructure. They can't rapidly spin up new projects because provisioning processes are unclear. They can't iterate quickly because infrastructure changes require cross-organizational coordination. They can't experiment because GPU availability is unpredictable.

This friction translates directly into reduced initiative velocity. A data science team that could launch a new model-serving project in two weeks with clear GPU infrastructure might need eight weeks when infrastructure ownership is ambiguous. Some of that time is actual technical work, but much is coordination overhead—waiting for approvals, clarifying responsibilities, documenting requirements, navigating organizational boundaries.

For organizations competing in markets where AI capabilities are strategic differentiators, this initiative delay has serious competitive implications. Competitors with clear GPU infrastructure ownership can experiment faster, iterate faster, deploy faster. They develop capabilities ahead of competitors with ownership ambiguity. They make mistakes faster, learn faster, win faster.

Additionally, ownership ambiguity creates talent retention problems. Data scientists and machine learning engineers want to focus on building models and solving problems. They don't want to spend time managing infrastructure. When GPU infrastructure is ambiguously owned, they spend significant time fighting with infrastructure rather than building products.

This frustration drives them toward competitors or toward organizations with clearer infrastructure stories. Organizations that can't retain experienced machine learning talent lose institutional knowledge and competitive capability.

The strategic cost of ownership ambiguity is often hidden in ways financial metrics don't capture well. Initiative delays show up as slower model deployments, which shows up as slower revenue growth. But the connection isn't always obvious to executives. Talent retention problems show up as reduced capability and higher hiring costs. But the connection between ownership ambiguity and talent departure often isn't explicit.

Nevertheless, the aggregate cost is substantial. Organizations with clear GPU ownership typically achieve higher innovation velocity and better talent retention.

Building Sustainable GPU Operations

Organizations successfully managing GPU infrastructure at scale treat GPUs as first-class infrastructure, no different in principle from databases, message queues, networking infrastructure. This means GPUs are provisioned through standardized processes. They're monitored with the same rigor as other infrastructure components. They have defined SLOs and operational standards. They're managed by teams with clear responsibility and accountability. They're documented thoroughly.

This first-class status means GPU infrastructure decisions are made strategically rather than reactively. Organizations should deliberately choose whether to prioritize cost optimization, performance optimization, or flexibility.

They should understand their GPU utilization patterns and consciously optimize for the patterns that matter. They should have capacity planning that anticipates future needs rather than constantly reacting to insufficient capacity. They should have disaster recovery plans ensuring GPU infrastructure availability and data resilience.

Building first-class GPU operations also means establishing reasonable operational standards. This might include requirements for monitoring and alerting on GPU utilization and failures. It might include requirements for documenting every GPU instance and its purpose. It might include regular capacity reviews identifying underutilized infrastructure. It might include regular security reviews ensuring GPU instances are configured securely.

These operational standards feel like overhead, but they're precisely what prevents the ownership ambiguity causing so many problems.

Platforms that abstract GPU infrastructure complexity enable organizations to achieve first-class operations status faster. By handling provisioning, monitoring, scaling, optimization, these platforms reduce the operational burden of GPU infrastructure management.

Organizations can focus on strategic decisions: which workloads matter most, what SLOs are appropriate, how to optimize for their specific business constraints, rather than on infrastructure details. This abstraction enables smaller organizations to operate GPU infrastructure at standards that would otherwise require large specialized teams.

The path to sustainable GPU operations starts with establishing clear ownership, but it extends far beyond that initial step. It requires sustained commitment to treating GPU infrastructure as critical infrastructure deserving the same investment and discipline as any other infrastructure category.

Organizations making this commitment find that GPU infrastructure becomes a capability strength rather than a source of organizational friction. Data science teams are productive because they have reliable, efficient infrastructure. Financial management is rigorous because they understand and control costs. Competitive position strengthens because they can innovate faster. The investment in clarity and discipline pays dividends across every aspect of GPU infrastructure operations.

Azumo helps enterprises establish clear GPU management ownership. Whether you need to build internal ML platform teams, extend DevOps capabilities, or adopt managed infrastructure that eliminates the ownership challenge entirely, we'll design the right model for your organization.

Schedule a free enterprise GPU assessment to identify ownership gaps and cost waste, or explore Valkyrie's managed GPU infrastructure to eliminate operational complexity entirely.

.avif)