We've watched this story unfold across hundreds of enterprises. A machine learning team discovers that API-based models from OpenAI or Anthropic can solve their immediate problem in days. Integration is straightforward, quality is impressive, and within a sprint or two, they have working prototypes demonstrating real business value.

Then comes the pivot: "This works, but we need to own the model. What about using open-weight alternatives like Llama or Mistral?"

So they launch a self-hosted LLM deployment initiative. They evaluate models, benchmark candidates that perform nearly as well as the API versions, create technical designs, request GPU infrastructure.

Then momentum stalls. Six months pass. Teams wrestle with GPU provisioning, serving framework decisions, integration complexity. Meanwhile, the original API system continues functioning reliably. The transition never happens. The enterprise pays for both systems.

We've seen this pattern so consistently it's become predictable. It's not poor engineering or bad decisions, it's a systematic consequence of how these deployment paths differ in operational complexity.

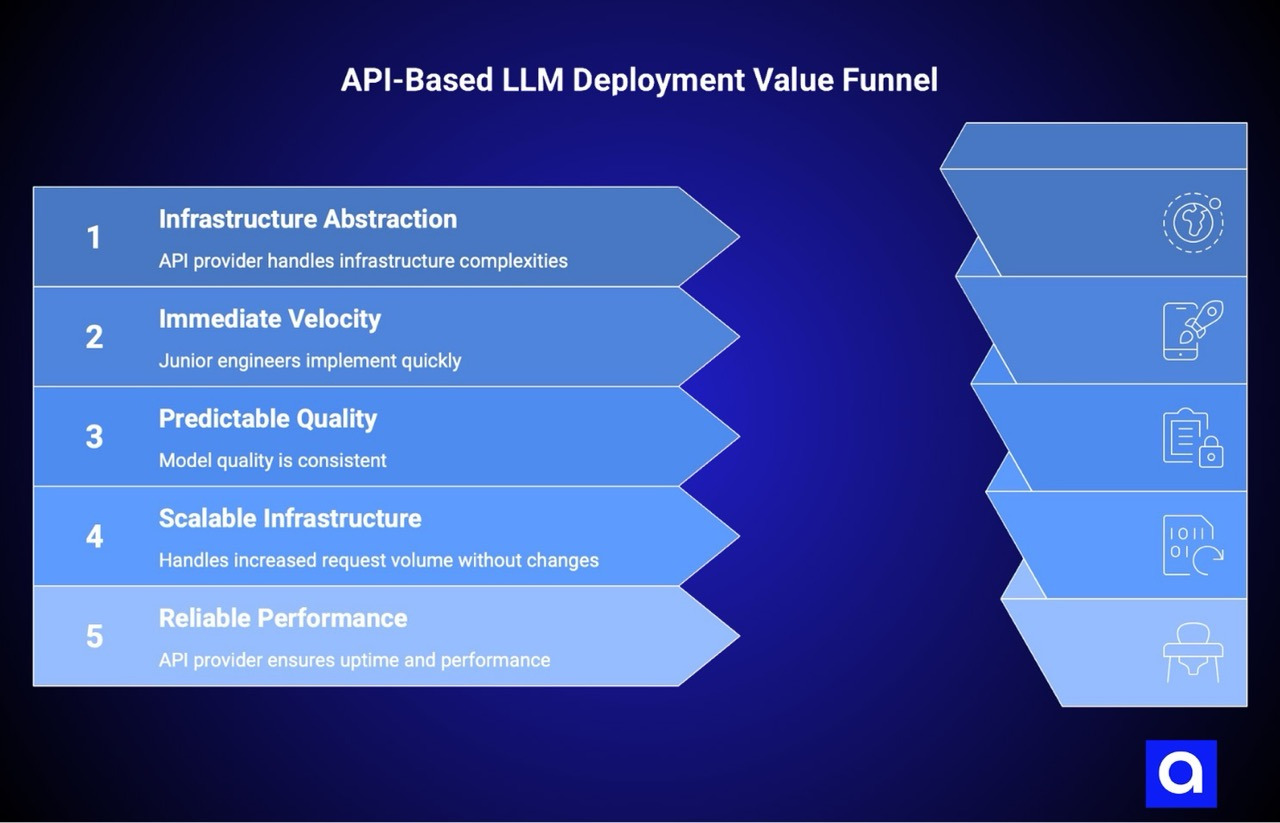

Why API-Based LLM Deployment Delivers Immediate Value

API-based LLM deployment wins early because API providers structure their offerings to abstract infrastructure problems. When we select an API model, we're not just getting a trained neural network. We're accessing solved infrastructure: optimized hardware at scale, concurrent request handling, model versioning, disaster recovery systems. All invisible to us.

This abstraction generates immediate velocity. A junior engineer implements an OpenAI API call in a single afternoon, complete with authentication, error handling, rate limiting. Model quality is predictable because the provider invested in training and alignment.

Scaling from one hundred to one million requests per day requires no infrastructure changes on our side. Upgrading models is a parameter change. The entire stack remains stable.

API providers align their incentives with our success. They've built observability, rate limiting, and cost tracking tools because customers need them. When something fails, there's a company legally responsible for uptime and performance.

This accountability creates reliability that's difficult to match when we're managing infrastructure ourselves. Operational complexity drops below what we anticipated, with fewer failure modes and clearer diagnostics.

API models aren't always the right long-term choice. But for the phase where we're validating that AI solutions solve real problems, API models have extraordinary advantages. They compress timelines dramatically. They don't require infrastructure expertise that might not exist yet on the team

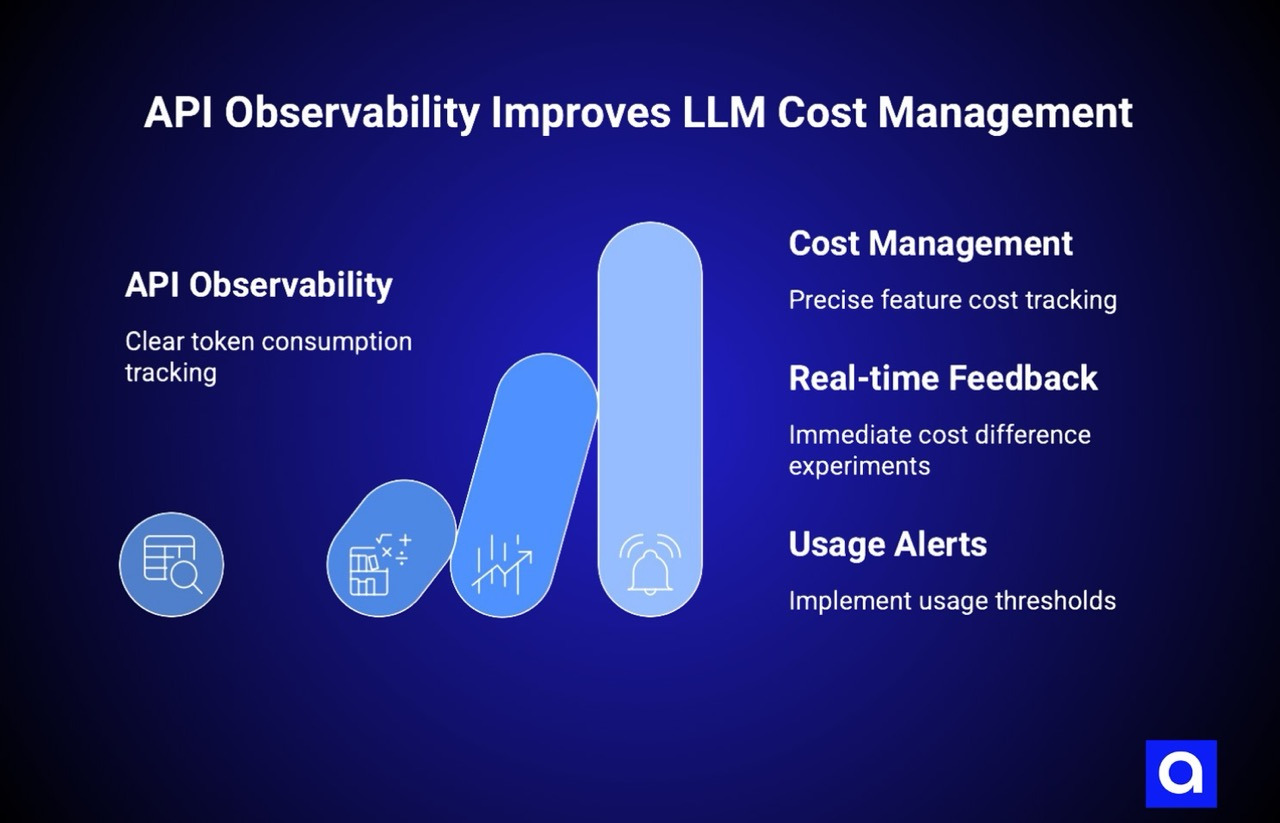

Operational Observability Extends Deeper Than Expected

One API advantage we frequently underestimate is cost tracking. Every token consumed generates a clear billing event. We can precisely track which features consume which models and exactly how much they cost.

This granularity enables cost management that's difficult with self-hosted systems. If a feature drives unexpected token consumption, we see it immediately. We can experiment with cheaper variants and see cost differences in real time. We can implement usage thresholds and alerts. The cost feedback loop is unambiguous.

Self-hosted systems rarely offer this transparency. We provision GPU infrastructure and then monitor utilization ourselves, estimating costs manually and tracking hardware expenses separately.

If a feature becomes less efficient, we might not notice for weeks. Integration libraries making inefficient requests remain invisible until we run detailed observability analysis. This opacity creates a dangerous dynamic where infrastructure costs become a black box requiring deep investigation for optimization.

Reliability patterns also favor API providers initially. Applications don't need sophisticated caching, batching, or request queuing—the provider's infrastructure handles this at scale. If providers experience issues, their entire business is affected, so they've invested heavily in redundancy.

When we self-host, these concerns become our responsibility. We decide between single instances or load-balanced clusters. We handle model crashes and restarts. We implement versioning and deployment procedures. Each introduces potential failure modes that API approaches don't have.

Why Open Weight Models Look Simple But Deployment Isn't

The case for open-weight models seems compelling. These models are genuinely impressive and improving rapidly. Licensing is favorable. Theoretical cost savings are significant if we can run models on owned hardware. At massive scale, this calculation makes sense. For most enterprises, the analysis isn't wrong, it's simply incomplete.

When our technical team evaluates a Llama or Mistral model and finds it performs well on benchmarks, we've conducted a valid experiment. The model truly works. But this success at the model level obscures deployment complexity.

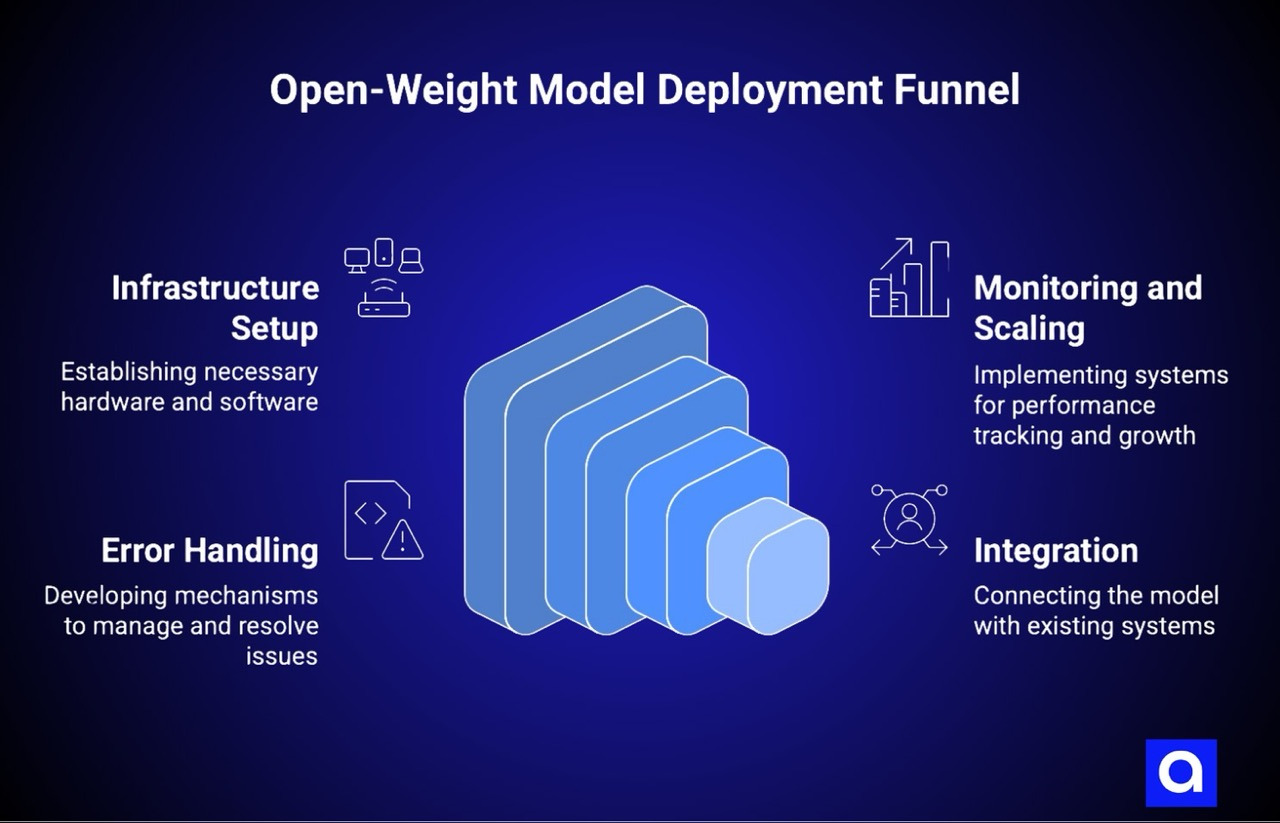

Deploying an open-weight model to production requires infrastructure, monitoring, scaling logic, error handling, integration points. Unlike most system components, model serving requires specialized hardware—GPUs, and the GPU infrastructure ecosystem is fractured. Organizations need comprehensive MLOps platforms to manage these operational complexities at scale

In our work with clients pursuing self-hosted models, we've seen this fragmentation become the root cause of most stalled initiatives. Deploying traditional application services follows well-trodden paths: Kubernetes on cloud infrastructure, standard monitoring, standard logging. Everyone understands these patterns developed over decades. GPU infrastructure is fundamentally different. The landscape is enormous.

Cloud providers each offer different GPUs at different prices with different performance characteristics. Serving frameworks number in the dozens: vLLM, TensorRT-LLM, Ollama, each with different strengths, weaknesses, learning curves.

This fragmentation creates a paralyzing decision problem. We can't simply decide "we'll use Llama" because a massive question remains unanswered: how will we actually run it? Every infrastructure decision cascades into others.

Choosing AWS commits us to their ecosystem. Choosing multiple clouds requires managing serving across cloud boundaries. Choosing on-premise means inheriting hardware procurement and maintenance. Each path adds substantial complexity that the API evaluation process initially glosses over.

GPU Provisioning Delays: Where LLM Deployment Timeline Stalls

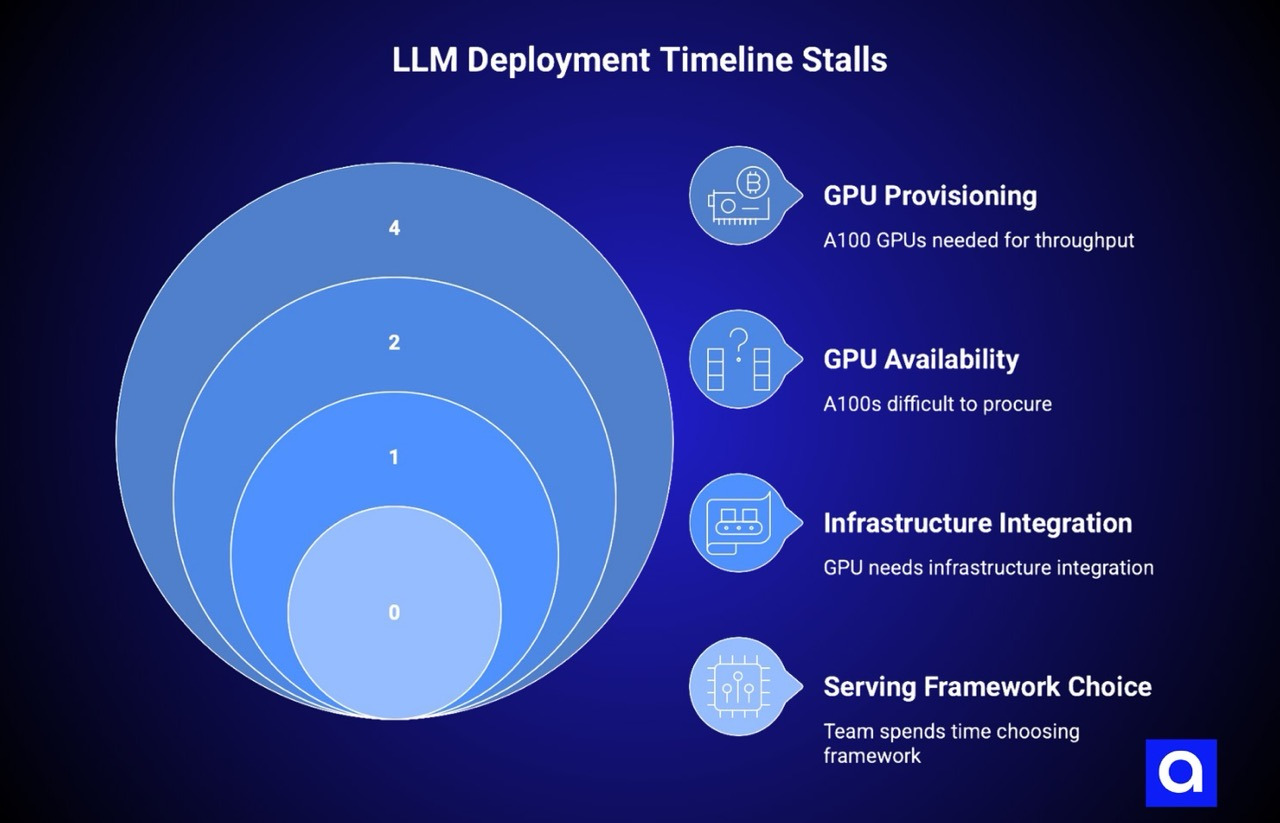

We've observed the first visible symptom of stalled LLM deployment timeline repeatedly: GPU provisioning delays. A team decides they need four A100 GPUs for adequate throughput. They request those GPUs through standard channels. Depending on the organization, this triggers several challenges.

Generic procurement teams unfamiliar with GPU economics might provision on cost-minimization basis rather than understanding performance requirements. Organizations managing data centers might need to purchase physical hardware, introducing lead times and capital approval processes.

Even when procurement eventually succeeds, the decision of where GPUs live creates cascading implications. AWS, Azure, GCP, or on-premise? Different choices mean vastly different latency, cost, integration with existing infrastructure, operational responsibility.

A team viewing GPU provisioning as straightforward suddenly discovers it's a strategic decision with massive ramifications. Procurement slows while decision escalates. Meanwhile, the API system continues functioning, serving real traffic, proving its value daily.

The provisioning delay intersects with another factor we've repeatedly observed: GPU availability itself. At any given time, certain models are in limited supply. A100s have been difficult to procure for extended periods. H100s have volatility.

If an organization tries provisioning a specific month and that GPU model isn't available, they choose between waiting weeks or accepting different specifications with different cost and performance characteristics. API-based systems never experience this. When providers update infrastructure, it happens invisibly. Compute capacity remains fungible with millions of other customers'.

Once GPUs finally arrive, they need infrastructure integration. If in AWS, they need the right service provisioning. If on-premise, they need network connectivity, power management, cooling, physical security.

This integration frequently reveals unexpected dependencies. Image registries might lack bandwidth for model containers. Network architecture might place GPUs in segments without database access. These aren't showstoppers, just delays. Each delay increases the gap between the working API prototype and the planned alternative.

We've observed teams spend surprising amounts of time choosing a serving framework. The decision seems straightforward initially, with options like vLLM, TensorRT-LLM, Ollama. But choosing isn't trivial. Each framework has different performance characteristics, stability properties, feature support, operational profiles.

vLLM offers excellent optimization for popular models but has a steeper learning curve and more complex deployment. Ollama emphasizes ease of use but might sacrifice performance. TensorRT-LLM offers maximum performance but requires substantial expertise.

The decision becomes paralyzing because these aren't just technical differences, they're commitments to learning curves and operational processes.

Choosing vLLM means investing in understanding vLLM's configuration, monitoring, optimization patterns. If later performance disappoints, switching frameworks costs. We'd need to re-benchmark, retrain staff, rebuild integration points. This decision gravity causes teams to deliberate extensively while the API continues running.

We've repeatedly seen teams encounter a gap between benchmarked and production performance. Models performing well in synthetic tests behave differently under real traffic. Real requests have different distributions. Concurrent patterns trigger different scaling behavior. Memory usage exceeds expectations, causing restarts. Initial GPU counts prove insufficient. Serving configuration needs tuning for specific traffic.

Teams then enter optimization cycles. They experiment with batch sizes, request prioritization, resource allocation parameters. Each experiment requires a deployment, testing period, analysis. During this time, teams engage actively with the open-weight initiative but don't deliver new features or value. The API system continues operating, proving its worth through reliable production operation. The comparison becomes harder to defend.

We've observed the final layer of friction emerges from integration. Deploying a model server is one thing. Integrating that server into application architecture is another. Applications need to handle model failures gracefully, manage rate limiting and load shedding, implement caching appropriately, route requests correctly, handle retries, manage version transitions.

These patterns aren't specific to open-weight models, but they're invisible when using APIs. The API provider handles all of this. Application code is simpler and more robust because complexity is externalized.

When we self-host, these patterns become our responsibility. Teams often underestimate this integration work. A straightforward serving framework deployment becomes substantially more complex once integrated into production application architecture.

Infrastructure Friction Compounds: The True Cost of Deployment Delays

Here's the critical insight transforming stalled initiatives from an interesting failure pattern into a strategic concern: infrastructure friction costs compound with time. A six-month delay in switching to open-weight models doesn't cost six months of development. It costs compounding opportunity costs.

Consider a team shipping two major features per quarter. They spend a month planning an open-weight migration, six months struggling with infrastructure friction, then deploy.

During those seven months, the API system enabled shipping eight features. Each feature drove user value, competitive advantage, revenue. The open-weight system provides lower infrastructure costs going forward, but those savings need to justify not just the infrastructure delay, but the feature velocity sacrificed during that delay.

Competitive implications compound this further. If competitors use APIs and ship features faster, they accumulate user experience advantages, develop more sophisticated capabilities, potentially achieve product-market fit first.

When the original team finally deploys open-weight infrastructure, they're deploying from a disadvantaged position. This dynamic explains why so many enterprises end up with stalled initiatives. They're not literally stalled from project management perspective. The team is actively working. But the velocity difference between moving fast with APIs and moving carefully with self-hosted infrastructure means the initiative gradually becomes less compelling.

Engineering velocity impacts expand beyond feature development. Teams spending months on infrastructure stabilization aren't available for operational improvements, refactoring work, emerging model research. Technical debt accumulates because team effort is consumed by infrastructure rather than code quality.

Organizations maintaining both API-based and self-hosted systems often find themselves unable to fully transition to self-hosted because the maintenance burden of two systems is substantial.

What Are The Underestimated Learning Curves of Self-Hosted LLM Deployment?

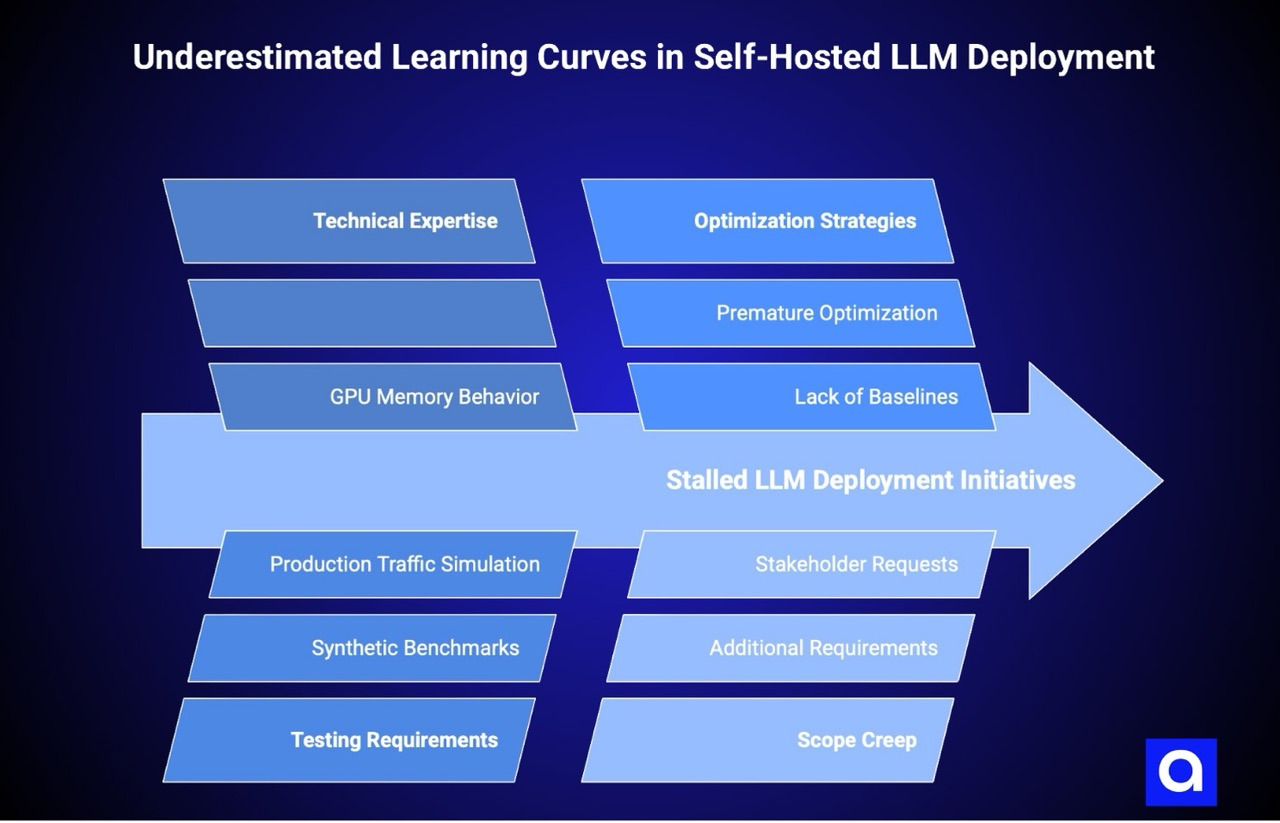

We've consistently observed the most common planning error: underestimating learning curves. Technical leaders often approach this as straightforward infrastructure deployment: select a model, select a serving framework, deploy it, integrate it. Operating open-weight models in production requires expertise that may not exist on the team.

Understanding GPU memory behavior, debugging serving framework configuration issues, optimizing model performance for specific hardware requires specialized knowledge.

This expertise gap becomes clear during implementation, not planning. Teams plan two weeks to select a serving framework and two weeks to deploy it. Actual implementation reveals that frameworks have subtleties and edge cases documentation doesn't emphasize. Configuration decisions seemingly straightforward have major performance implications. Debugging requires understanding not just framework intended behavior, but how it interacts with specific infrastructure, model, and traffic patterns.

Organizations sometimes address this by hiring specialized infrastructure engineers. This works but delays timeline and adds cost. Other organizations assume the team will learn, creating schedule overruns. Both outcomes contribute to stalled initiatives—one from hiring complexity, the other from extended timelines as learning happens in parallel with development.

We've also observed organizations underestimate testing requirements before shifting production traffic. Testing whether a model serves requests quickly enough requires simulating production-like traffic, not synthetic benchmarks. Synthetic benchmarks are useful, but they don't capture production characteristics.

Real users send requests at unpredictable intervals. Real requests sometimes have unusual properties triggering worst-case framework behavior. Real traffic has burst periods and idle periods. Testing not reflecting these patterns leads to production surprises.

Proper testing requires time and careful measurement. Teams might need to shadow the API system for weeks, comparing results and monitoring behavior before switching traffic. Comprehensive LLM model evaluation becomes essential when comparing self-hosted performance against API baselines. This phase frequently reveals issues requiring optimization cycles. The testing phase wasn't planned in most initial timelines because it seems simple, but production-grade testing never is.

We've seen teams encounter another self-inflicted delay: pursuing optimization before establishing stable baselines. Teams deploy serving frameworks and immediately begin tuning batch size, memory allocation, request prioritization, dozens of other parameters.

This optimization work is valuable long-term but extends initial deployment timeline. It's often more productive to deploy reasonably-configured systems, measure behavior under production load, optimize incrementally.

But teams frequently want to optimize before going live, partly because they've heard model serving optimization is critical and partly from anxiety about performance.

Configuration complexity creates another pattern: teams feel pressure to configure systems to theoretical maximum capacity, adding features not yet needed. Serving frameworks might offer sophisticated batching algorithms, custom request routing, complex caching strategies.

Using all these features immediately multiplies configuration complexity, testing requirements, operational learning curve. Simpler initial configurations with additional complexity added only when needed would accelerate deployment. But infrastructure engineers often find it appealing to implement full complexity upfront.

We've frequently observed scope expand in ways that delay timeline. Initial scope might be "deploy Llama 2 to handle customer support queries." As teams work, they identify additional requirements. Should the system handle multiple models? Should it implement sophisticated caching? Should it integrate with fine-tuning pipelines? Each additional requirement adds complexity and timeline.

This scope creep happens because teams become more sophisticated about what's possible as they work through infrastructure. But it also happens because stakeholders see model serving systems under development and immediately request features. Teams that could ship basic deployment in three months find themselves six months in still working on expanded requirements.

Organizations successfully transitioning to open-weight models typically establish clear success criteria before committing to infrastructure work.

These criteria look like: "The self-hosted system must serve requests with less than X latency," "It must handle at least Y requests per second," "Operational overhead must be less than Z hours per week," "Infrastructure cost must be less than W per month."

These specific, measurable criteria provide targets that teams optimize toward, providing stopping points for optimization work.

Without clear success criteria, optimization continues indefinitely. Teams can always make systems faster, cheaper, more reliable. With explicit criteria, we can deploy as soon as meeting targets. This discipline prevents the endless optimization cycle characterizing stalled initiatives.

Clear criteria also provide decision points for evaluating whether transition makes sense. Some teams begin open-weight initiatives and discover that API solutions meet their needs better than anticipated.

With clear criteria, this realization leads to deliberate decision to continue with APIs rather than forcing unnecessary transition. Without criteria, teams feel obligated to complete transition because they've already invested time.

Hybrid LLM Deployment: Combining API Speed with Self-Hosted Scale

Rather than treating API LLM deployment and self-hosted systems as binary choices, successful transitions use hybrid architectures. A common pattern: deploying the self-hosted model to handle highest-volume use cases where per-inference cost savings are most significant, while keeping APIs for lower-volume, more variable use cases.

This approach reduces infrastructure burden because we don't need to provision capacity for peak loads across all use cases. It enables gradual transition: we can shift traffic incrementally to self-hosted systems as confidence builds.

Hybrid architectures also provide risk mitigation. If self-hosted systems encounter issues, APIs serve as fallback capacity. This safety net reduces pressure to over-provision or over-optimize.

Teams can deploy with realistic baselines, measure production behavior, optimize incrementally. This approach typically compresses timelines by removing the all-or-nothing pressure characterizing initial deployments.

Another hybrid pattern: using APIs for development and testing, deploying to self-hosted for production. This approach keeps development cycles fast because developers can experiment with APIs without worrying about infrastructure. Production deployments use self-hosted systems for cost efficiency.

This separation can reduce team friction and accommodate different preferences within the organization.

How Do Platforms Reduce Infrastructure Friction?

Some organizations tackle infrastructure complexity by adopting platforms designed to abstract GPU infrastructure management. These platforms handle GPU provisioning, model serving framework selection, scaling, operational monitoring. They substantially reduce the specialized expertise required to operate self-hosted models.

In our experience, platforms like Valkyrie particularly address the provisioning bottleneck. Instead of teams spending weeks acquiring GPUs through traditional channels, the platform handles provisioning, often with access to spot instances, reserved capacity, and multi-cloud options that reduce cost and improve availability.

Instead of teams deciding between AWS, Azure, and on-premise, the platform makes those decisions based on cost and availability. Instead of teams learning vLLM or TensorRT-LLM, the platform operates the serving framework and provides simple interfaces.

The value becomes particularly clear when understanding why traditional infrastructure choices create delays. Teams using platforms still need to select a model and define requirements. But most friction points causing initiatives to stall are eliminated. GPU provisioning becomes fast because platform relationships with providers accelerate it.

Serving framework selection becomes simpler because platforms standardize on frameworks and handle configuration. Integration becomes simpler because platforms provide standard APIs. Performance optimization becomes faster because platforms implement sophisticated optimization strategies.

Platforms don't eliminate all complexity. Operating models at scale still requires understanding workload characteristics, defining SLOs, making tradeoffs between cost and performance. But platforms collapse infrastructure overhead into something manageable by general infrastructure teams without specialized GPU expertise.

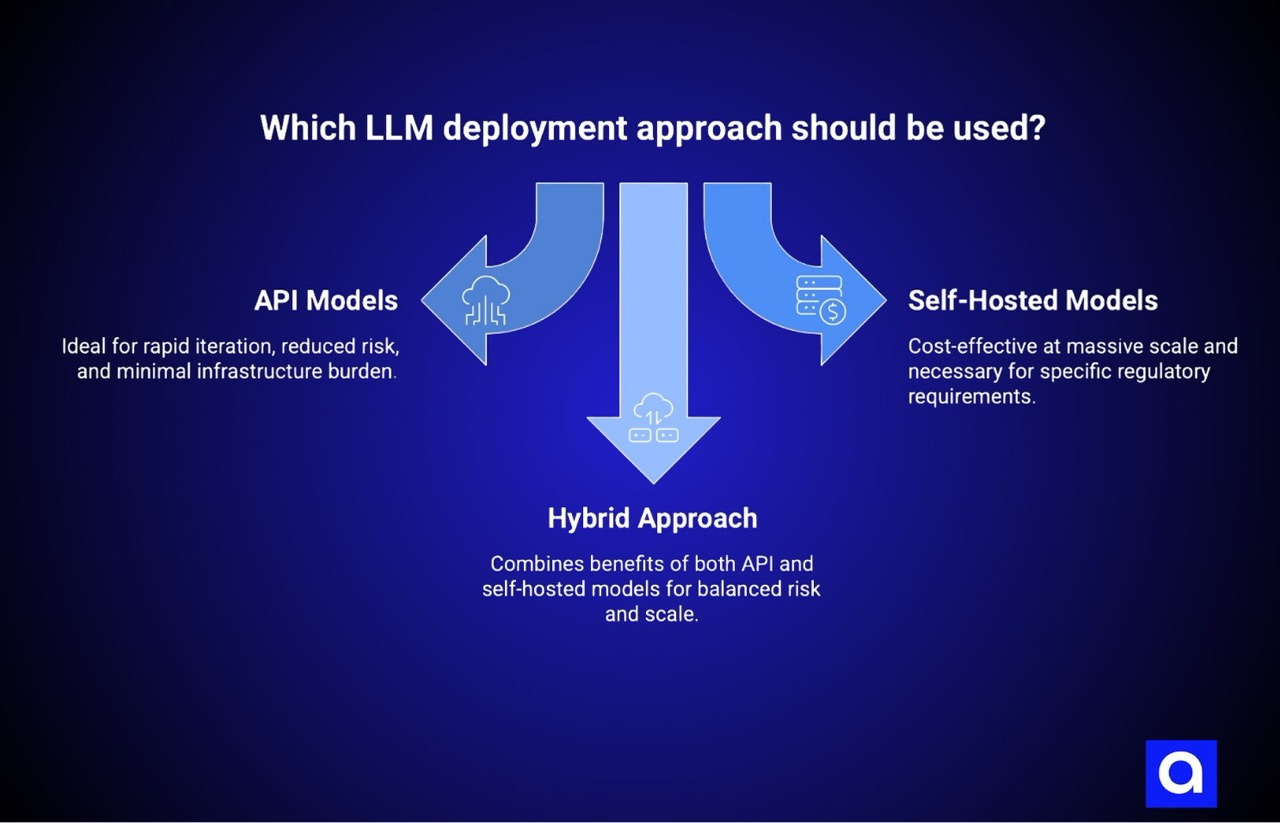

LLM Deployment Decision Framework: API vs Self-Hosted vs Hybrid

The question "should we use API models or self-hosted open-weight models" doesn't have a universal answer. Specific circumstances suggest different approaches. If we're exploring whether AI solutions solve real problems, if our team lacks specialized GPU expertise, or if feature velocity is a critical constraint, API models typically make sense. They compress timelines and reduce risk. They enable rapid iteration and reduce infrastructure burden.

If we operate at massive scale processing millions of inferences monthly, self-hosted models often make financial sense. At that scale, API per-inference costs eventually exceed self-hosted costs even accounting for operational overhead.

If we have specialized infrastructure teams with GPU expertise, we've already resolved one of the major constraints causing initiatives to stall. If we have specific regulatory requirements around data residency or model ownership, self-hosted systems might be necessary. However, most organizations benefit from working with experienced AI development companies that have deployed production LLM infrastructure across multiple clients.

The framework for deciding: estimate both timeline and total cost of ownership for each approach. Timeline cost includes not just calendar time to deployment, but opportunity cost of engineering effort consumed by infrastructure. Total cost of ownership includes not just hardware costs, but operational staff, specialized training, cost of system failures. In many cases, this analysis reveals that APIs are cost-effective far longer than initial financial models suggest.

Some organizations benefit from hybrid approaches: using APIs for development and small-scale production workloads, transitioning to self-hosted for high-scale workloads. This approach captures benefits of both models and reduces risk that purely self-hosted transition will stall indefinitely.

Moving Forward Pragmatically

The pattern of stalled open-weight initiatives often reflects tension between different organizational values. Technical infrastructure teams often favor owning systems end-to-end and optimizing them thoroughly.

This preference is understandable and valuable. But it can conflict with product development teams' emphasis on velocity and delivering user value rapidly. When infrastructure ideology becomes the primary decision criterion, initiatives often stall because the organization optimizes for infrastructure purity rather than business outcomes.

Organizations successfully navigating this tension maintain pragmatic decision-making. They ask "what approach delivers value to customers fastest?" rather than "what approach is technically most sophisticated?" They recognize that answers change as circumstances change.

Early-stage AI products almost always benefit from API approaches because the risk is learning whether AI solves real problems, not optimizing infrastructure costs. Once product-market fit is established and scale increases, self-hosted approaches become increasingly attractive.

The most effective approach is explicit acknowledgment of this evolution. Rather than planning single infrastructure architecture, plan for evolution. Start with APIs, establish clear criteria for transitioning to self-hosted systems, execute the transition when criteria are met.

This approach typically achieves both rapid early deployment and cost efficiency at scale while avoiding the trap of stalled initiatives consuming resources without delivering corresponding value.

The goal isn't declaring APIs or self-hosted models universally superior. The goal is recognizing that these approaches have different strengths in different contexts, and that successful organizations make deliberate choices rather than defaulting to infrastructure ideology.

Teams understanding these tradeoffs explicitly rarely find themselves maintaining stalled initiatives. They either commit to one approach and optimize it thoroughly, or they design hybrid architectures capturing benefits of both.

The distinction between successful approaches and stalled initiatives often comes down to clear decision-making early, explicit success criteria, willingness to revise plans as circumstances change.

.avif)