The story repeats across organizations attempting to deploy open-weight AI models in production.

A small team of talented engineers discovers an open-weight AI model that seems perfect for an organization's needs. The model produces impressive results in a controlled environment. Inference latency is reasonable, output quality meets expectations, and the cost appears manageable.

The team puts together a demo where the model solves a realistic business problem. Executives are impressed. A timeline is created: eight weeks to production, perhaps ten if we're conservative. Stakeholders are informed that this model will be deployed within two months. The project is approved, resources are allocated, and work begins in earnest.

Three months later, the project is still in development. The timeline has slipped to sixteen weeks. Stakeholders are confused about what happened. The engineers are frustrated and working nights and weekends. The demo that worked perfectly now works inconsistently. What appeared to be an eight-week deployment was, in reality, a prototype-to-production gap that no one planned for.

By month six, some organizations abandon the project entirely, moving back to proprietary models or pushing the decision into the indefinite future. Others persist, finally reaching production nine to twelve months after the initial estimate, burned out and over budget.

The pattern repeats across organizations attempting to deploy open-weight AI models into production. The transition from prototype to production proves far more difficult than anticipated, not because the underlying models are flawed but because prototypes and production systems operate under entirely different constraints and requirements.

A prototype can be trained and evaluated on curated datasets, run on powerful workstations, respond slowly if necessary, consume large amounts of computational resources, and be restarted when something breaks. Production systems must serve real users at scale, must maintain consistent performance, must handle variable input patterns, must operate within cost budgets, and must not fail completely. The engineering effort required to bridge the gap between prototype and production is often ten times greater than the effort to develop the prototype itself, yet organizations consistently underestimate this gap.

Understanding where projects fail and what distinguishes projects that succeed offers essential guidance for organizations planning to deploy open-weight AI models. We've identified failure modes across three dimensions: infrastructure failures that occur when organizations attempt to serve open-weight models at scale, operational failures that emerge when production systems encounter requirements beyond laboratory conditions, and organizational failures that arise when projects lack clear ownership and accountability.

Recognizing these failure modes in advance, and planning explicitly to address them, separates projects that successfully reach production from projects that stall indefinitely.

Why Open-Weight AI Prototypes Break in Production Environments

The fundamental reason that prototypes transition so poorly to production is that prototype environments are fundamentally different from production environments in ways that are invisible to the engineers building the prototype.

A single engineer on a powerful workstation running an open-weight language model enjoys circumstances that are completely unlike those of a production system serving thousands of users. These differences represent fundamentally distinct operational regimes.

In a prototype environment, the engineer has complete control over inputs and can optimize specifically for those inputs. If the engineer is developing a question-answering system, they can test the model with carefully crafted questions that stay within the model's strong performance zones.

The engineer can select the datasets, curate examples, and eliminate edge cases. The model processes one request at a time, takes as long as needed to generate responses, and the engineer waits patiently for the results.

If something goes wrong—if the model produces incorrect output, crashes, or behaves unexpectedly—the engineer restarts the system and tries again. There is no notion of service level agreements or availability guarantees. The engineer simply wants results, and they are willing to work around minor issues to get them.

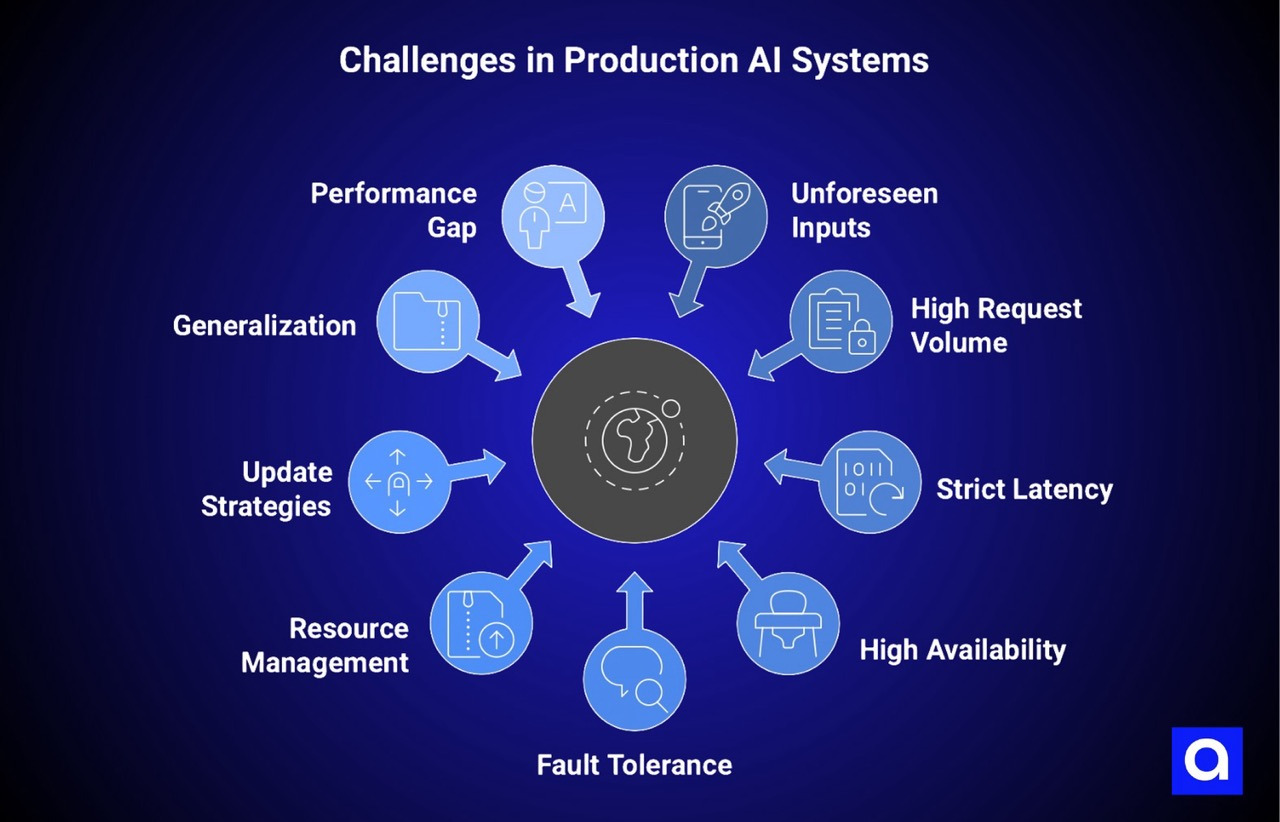

Production AI Systems Operate Under Strict Latency, Reliability, and Scale Constraints

In production, an open-weight AI system must handle the full universe of possible inputs without advance knowledge of what those inputs might be. Real users ask questions that the engineers never anticipated, in languages and formats the model was not specifically tested against, with assumptions about how the model should behave that the engineers never made explicit.

The system must process thousands or millions of requests daily, many arriving simultaneously. Each request must be answered within strict latency constraints; if a user's question is not answered in two seconds, they will perceive the system as broken regardless of whether the model would eventually produce a correct answer.

The system must maintain availability above 99.9 percent; a system that is unavailable even one percent of the time is unavailable thousands of times each day when processing millions of requests. If the system fails, it must fail gracefully and maintain whatever partial service is possible.

These differences force fundamentally different engineering approaches. A prototype can be built in whatever language the engineers are comfortable with, using whatever libraries and frameworks seem convenient at the moment.

Production systems must be built with explicit consideration for fault tolerance, graceful degradation, monitoring, and operational support.

A prototype can allocate computational resources however seems convenient; a single GPU might be perfectly adequate.

Production systems must carefully manage computational resources to serve multiple users simultaneously while staying within cost budgets.

A prototype can be restarted whenever the engineer wants to update it or fix bugs; production systems must implement careful update strategies that minimize impact to users.

The controlled scenario advantage that prototypes enjoy is often underestimated in its importance. When an engineer develops a prototype, they are usually solving a narrowly defined problem with well-understood characteristics.

The engineer might build a system that generates product descriptions from specifications, or a system that analyzes medical images in a specific context, or a system that summarizes legal documents of a certain type. The model is trained and tuned specifically for this narrow problem. In production, the system must be more general.

Real users will attempt to use the system for purposes it was not specifically optimized for. They will input data that does not match the training distribution. They will ask questions that require knowledge or reasoning beyond what the model was designed to perform.

A model that achieves ninety-five percent accuracy on carefully curated test data might achieve seventy percent accuracy on real-world user inputs. This gap reflects not a failure of the model but rather the gap between how well-defined problems are in prototype environments and how messy they are in production.

The engineer developing the prototype may have been working on a very specific problem and may have optimized the model specifically for that problem. Production users will attempt to apply the model more broadly, and the model's performance will degrade when applied outside its optimization zone.

Bridging this gap requires substantial engineering effort: better error handling, fallback mechanisms, reranking and verification stages, and careful monitoring to identify when the model is performing poorly.

Performance expectations similarly differ dramatically between prototypes and production. An engineer testing a model on a workstation might accept a response time of several seconds. If the model takes five seconds to process a request, that is perfectly acceptable in an interactive development environment.

In production, five-second response times are often unacceptable. Users expect responses in under a second for most applications. Even two seconds can feel slow and cause users to abandon the interaction.

Meeting production latency requirements often requires entirely different infrastructure approaches: model quantization or distillation to reduce computational requirements, specialized serving frameworks optimized for inference, architectural patterns that minimize latency, and careful resource allocation to ensure that responses are fast even when the system is under high load.

These optimizations often introduce their own complexity and require careful engineering to implement correctly.

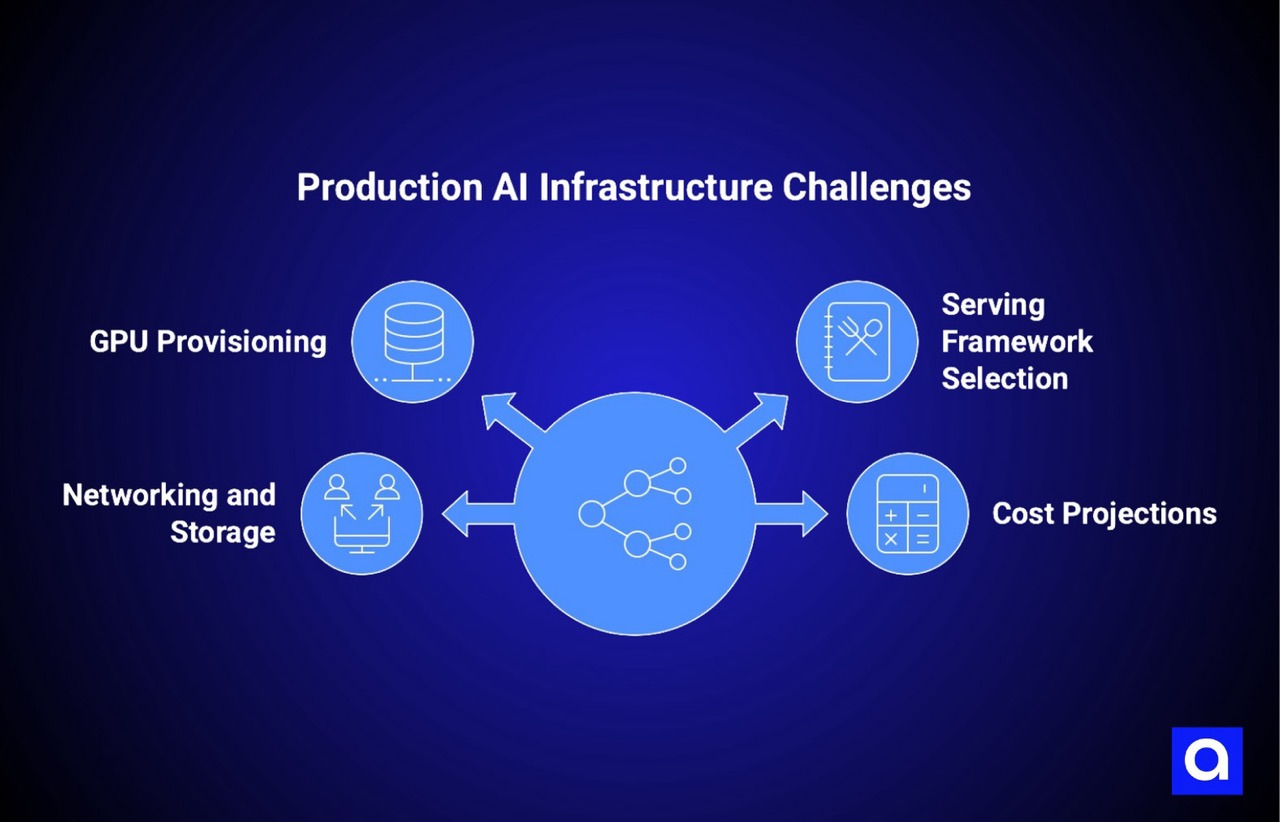

What Are The Hidden Infrastructure Costs of Serving Open-Weight AI at Scale?

The transition from prototype to production surfaces infrastructure challenges that developers rarely encounter in prototype development. These challenges cluster into several categories: GPU provisioning and resource management, serving framework selection, networking and storage architecture, and cost projections that prove wildly optimistic.

GPU provisioning represents the first major challenge that organizations face when attempting to move from prototype to production. In a prototype environment, an engineer has access to a single powerful GPU, or perhaps a few GPUs in a local development cluster. The engineer's code is optimized for this specific GPU, with all model weights and intermediate activations stored in that GPU's memory. The prototype works beautifully as long as the model fits in the available GPU memory and the computational load is reasonable.

In production, the situation becomes far more complex. Production systems must serve multiple users simultaneously, which means multiple requests must be processed in parallel. A model that requires twenty gigabytes of GPU memory for a single inference pass now needs sufficient GPU memory to handle multiple concurrent requests. A model that can process one request per second on a single GPU must now handle hundreds or thousands of requests per second across a cluster of GPUs.

This shift from single-GPU to multi-GPU infrastructure introduces complexity in every direction. Model serving frameworks must handle request batching, distributing requests across GPUs efficiently, managing memory carefully to avoid out-of-memory errors, and maintaining optimal throughput while managing latency. Some frameworks handle this better than others.

Selecting the right serving framework is not a trivial decision; different frameworks optimize for different scenarios and make different tradeoffs between latency, throughput, and ease of implementation. TensorFlow Serving is optimized for TensorFlow models and handles many production scenarios well. Triton Inference Server supports multiple frameworks and provides sophisticated batching and scheduling. Text generation frameworks like vLLM are specifically optimized for language models.

Selecting the wrong framework can mean the difference between a system that reaches production with reasonable engineering effort and a system that requires extensive customization and integration work.

Beyond serving frameworks, the question of GPU provisioning itself becomes operationally complex. A production system must decide how many GPUs to allocate to handle peak load, but predicting peak load for a new system is notoriously difficult. Allocate too few GPUs and the system becomes slow and unreliable during high-traffic periods. Allocate too many GPUs and the system is expensive to operate.

Most organizations solve this through scaling, but scaling introduces its own challenges. Cloud-based GPU provisioning is fast in absolute terms but can take minutes to add new GPUs to a cluster, which is too slow to respond to sudden traffic spikes.

On-premises GPU infrastructure requires capital investment upfront and cannot easily scale down if demand decreases. Hybrid approaches that maintain a baseline of on-premises GPUs and burst to cloud GPUs during peak periods introduce integration complexity and cost management challenges.

The serving framework selection problem encompasses a much larger set of decisions than simply choosing a software package. Once a serving framework is selected, the organization must implement the framework, integrate it with the broader application architecture, manage model updates and versioning within the framework, and ensure that the framework meets the organization's latency and throughput requirements.

These decisions are made against a background of uncertainty; the organization cannot know in advance exactly what serving requirements production will impose. A framework that seems perfectly adequate during evaluation might prove inadequate when facing real traffic patterns.

Organizations often discover partway through production that they selected the wrong framework and must migrate to something else, a process that can take weeks or months of engineering time.

Networking and storage decisions similarly become vastly more complex at production scale. A prototype might store model weights on the same machine that runs inference, or might load them from a local disk.

In production, model weights must be loaded quickly, must be available even if one machine fails, and must be updated efficiently when model versions change. This typically requires shared storage infrastructure: network-attached storage or distributed storage systems that allow multiple machines to access model weights simultaneously.

Selecting and operating appropriate storage infrastructure, ensuring adequate bandwidth for model loading, and designing update procedures that do not cause service disruptions all add significant complexity.

Network architecture decisions similarly differ between prototype and production. A prototype might run on a single machine with network connectivity to external systems as needed.

A production system likely spans multiple machines or regions, which requires careful network design to ensure low-latency communication between components, sufficient bandwidth to handle concurrent requests, and graceful handling of network failures.

If the system spans geographic regions to minimize latency or improve resilience, additional complexity appears in the form of consistency requirements, data synchronization, and failure modes that arise from geographic distribution.

Cost projection failures represent perhaps the most painful infrastructure challenge for organizations deploying open-weight models to production. The economics of serving open-weight models can be counterintuitive and difficult to predict.

A prototype running on a single GPU with reasonable utilization might process one thousand requests daily with trivial cost. The same model serving production traffic might require a cluster of ten GPUs to maintain acceptable latency, raising cost by an order of magnitude or more.

If the organization initially underestimated the serving infrastructure required, this cost surprise can be significant. An organization that thought it could serve models for dollars per day might discover the true cost is thousands of dollars per day. This cost shock has derailed many open-weight model deployments.

Several factors conspire to make cost projections optimistic.

First, prototype-to-production scaling is not linear. A model that is acceptable in a prototype might require significant optimization to perform acceptably in production. These optimizations—model distillation, quantization, architectural changes—all require engineering time and might require retraining or fine-tuning the model.

Second, the cost of inference scales with latency requirements. A model that can take five seconds to respond costs far less to serve than a model that must respond in under one second, because latency requirements force the use of more expensive serving infrastructure.

Third, the cost of inference varies wildly depending on infrastructure choices. Cloud-based GPU pricing is higher than on-premises GPU infrastructure but offers flexibility.

Specialized serving infrastructure like inference accelerators or custom silicon might be more cost-effective than general-purpose GPUs but requires additional engineering effort to integrate. Most organizations do not fully account for these cost drivers until they are deep in production.

What Are The Operational Failures That Appear Only After Open-Weight AI Reaches Production?

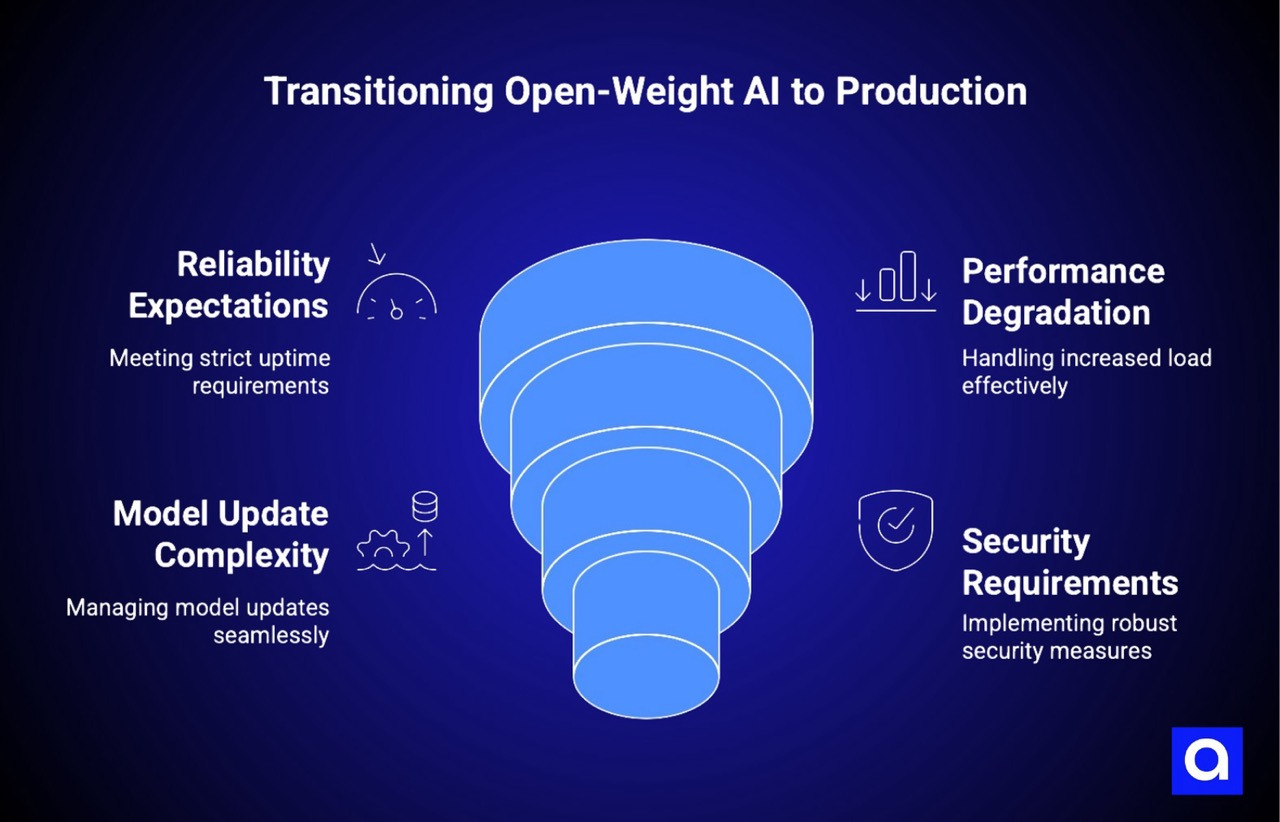

Beyond infrastructure challenges, the transition to production surfaces operational requirements that prototypes are typically not designed to handle. These requirements include reliability expectations, performance degradation under load, model update complexity, and security requirements that emerge only in production.

Reliability expectations in production are orders of magnitude stricter than in prototype environments. A prototype that is available ninety percent of the time is perfectly acceptable because prototypes are designed for development and evaluation, not for serving users.

A production system that is available only ninety percent of the time fails thousands of times daily when processing millions of requests. Users quickly learn not to trust the system and stop using it. Reliability requirements of 99.9 percent or higher are typical for production systems.

Achieving this level of reliability requires extensive engineering: redundancy at every level so that failures in one component do not cause system outages, careful monitoring to identify problems early, automated failover systems, and extensive testing of failure modes.

Many open-weight models were not designed with production reliability in mind. They were designed for research and evaluation where occasional failures are acceptable. When these models are placed into production, reliability issues surface that were not apparent in development.

A model might occasionally produce outputs that cause downstream processing to fail. Depending on the specific use case, this might be a crash in the application logic, an error in data pipeline processing, or a response that is unusable or offensive.

In a prototype, these occasional failures are noticed by the engineer developing the system and handled manually. In production, occasional failures occur thousands of times daily and must be handled automatically through robust error handling, fallback mechanisms, and graceful degradation.

Performance degradation under load represents a second operational challenge that surfaces only in production. A model that performs beautifully when processing one or two requests per second might behave unexpectedly when processing hundreds of requests per second.

Different batching strategies might be required. Memory management becomes crucial; insufficient memory management can cause garbage collection delays that introduce unpredictable latency spikes. Concurrent request handling can expose subtle bugs that never appeared in sequential processing. Load balancing across multiple GPUs must be carefully tuned to avoid bottlenecks.

These performance challenges often require profiling and optimization work that was unnecessary in prototype environments.

Model update complexity represents a third operational challenge specific to open-weight models. Organizations deploying open-weight models to production must address how to update models when improved versions become available, when the organization wants to fine-tune models with additional data, or when security vulnerabilities are discovered in existing models.

In a prototype, updating a model is trivial; simply retrain the model with new data and restart the service. In production, model updates must be handled carefully to minimize disruption to users. A production system typically maintains multiple versions of a model and gradually transitions traffic from old versions to new versions, monitoring performance carefully and rolling back to previous versions if problems are discovered.

This process requires sophisticated deployment infrastructure, careful version management, and extensive testing of new model versions before they serve production traffic.

Security requirements similarly emerge or intensify in production. A prototype might not need to consider adversarial attacks, prompt injection attacks, or other security threats because it is not exposed to adversaries.

A production system serving real users must consider these threats seriously. Open-weight models are particularly vulnerable to certain categories of security attacks. Language models can be manipulated through prompt injection to ignore their training objectives and generate inappropriate content. Vision models can be fooled by adversarial examples designed to misclassify inputs.

Production deployments of open-weight models must implement security measures to mitigate these risks: input validation, output filtering, monitoring for suspicious patterns, and rapid response mechanisms when attacks are detected.

What Are The Organizational Failures That Stall Open-Weight AI Deployments?

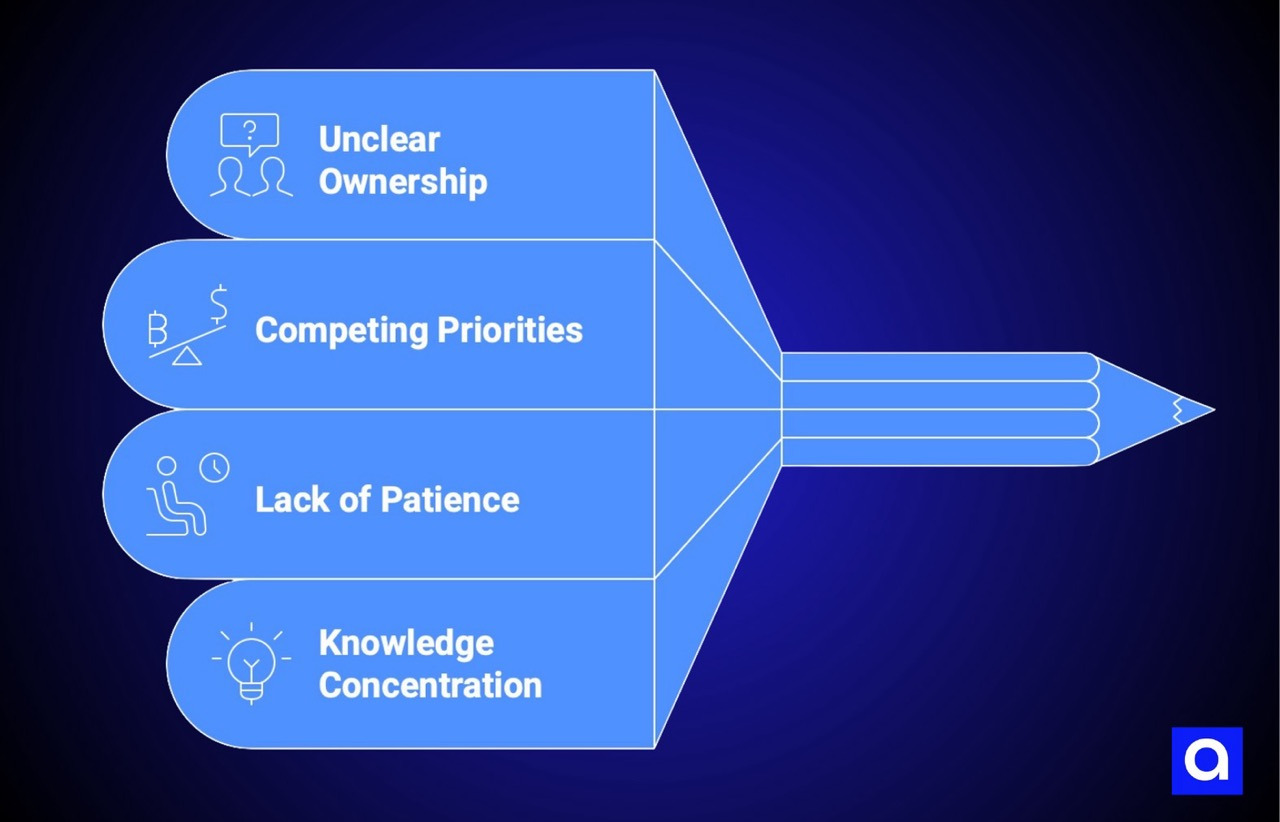

Beyond technical infrastructure and operational challenges, many open-weight deployments fail for organizational reasons. These failures include unclear ownership, competing priorities, misaligned incentives, and lack of organizational patience and commitment.

Unclear ownership represents a surprisingly common organizational failure mode. When an organization decides to deploy an open-weight model, responsibility often falls somewhere in the gray area between research and engineering.

The research team that discovered the model and built the prototype is passionate about seeing it reach production but often lacks the infrastructure and operational expertise to deploy it.

The engineering team that has the expertise to build production systems is unfamiliar with the model and uncertain about the effort required to make it production-ready.

Neither team owns the project fully; responsibility is shared, which in many organizations means that no one truly owns it. When conflicts arise between the prototype requirements and production requirements, there is no clear decision maker.

The project stalls as the teams navigate organizational politics and unclear accountability.

Competing priorities within the engineering organization similarly stall many projects. An engineering team that is supporting a prototype deployment of an open-weight model is simultaneously responsible for maintaining existing systems, implementing new features requested by customers, and responding to operational crises.

When these competing demands exist, production deployment of new models often loses out. Existing systems generate revenue and have established customers; new systems generate hypothetical future value.

The engineering organization rationally prioritizes time spent on existing systems over experimental deployment of new models. The open-weight model deployment slips in priority, the timeline extends, and momentum is lost.

Executive patience and organizational commitment represent additional challenges. Organizations often approve open-weight model deployments based on optimistic timelines that prove completely unrealistic.

When the eight-week timeline extends to sixteen weeks, and then to six months, executive patience wears thin. Executives question whether the project is viable, whether different approaches might be faster, whether resources would be better spent elsewhere.

These questions are sometimes reasonable, but they often come at the moment when the infrastructure challenges are becoming clear but before the organization has invested enough effort to see the benefits of continuing. Projects that require persistence and additional resources to reach production are sometimes cancelled when executives lose confidence in the timeline.

Knowledge concentration and expertise dependency represents a subtle but serious organizational failure mode.

If a single engineer understands the entire pipeline for deploying and serving the open-weight model, that engineer becomes a critical bottleneck.

If the engineer leaves the organization, takes on other responsibilities, or becomes unavailable, the project stalls. Organizations that fail to distribute knowledge and responsibility across multiple team members often find that their open-weight projects are entirely dependent on specific individuals. When those individuals become unavailable, progress stops.

What Successful Open-Weight AI Production Teams Do Differently

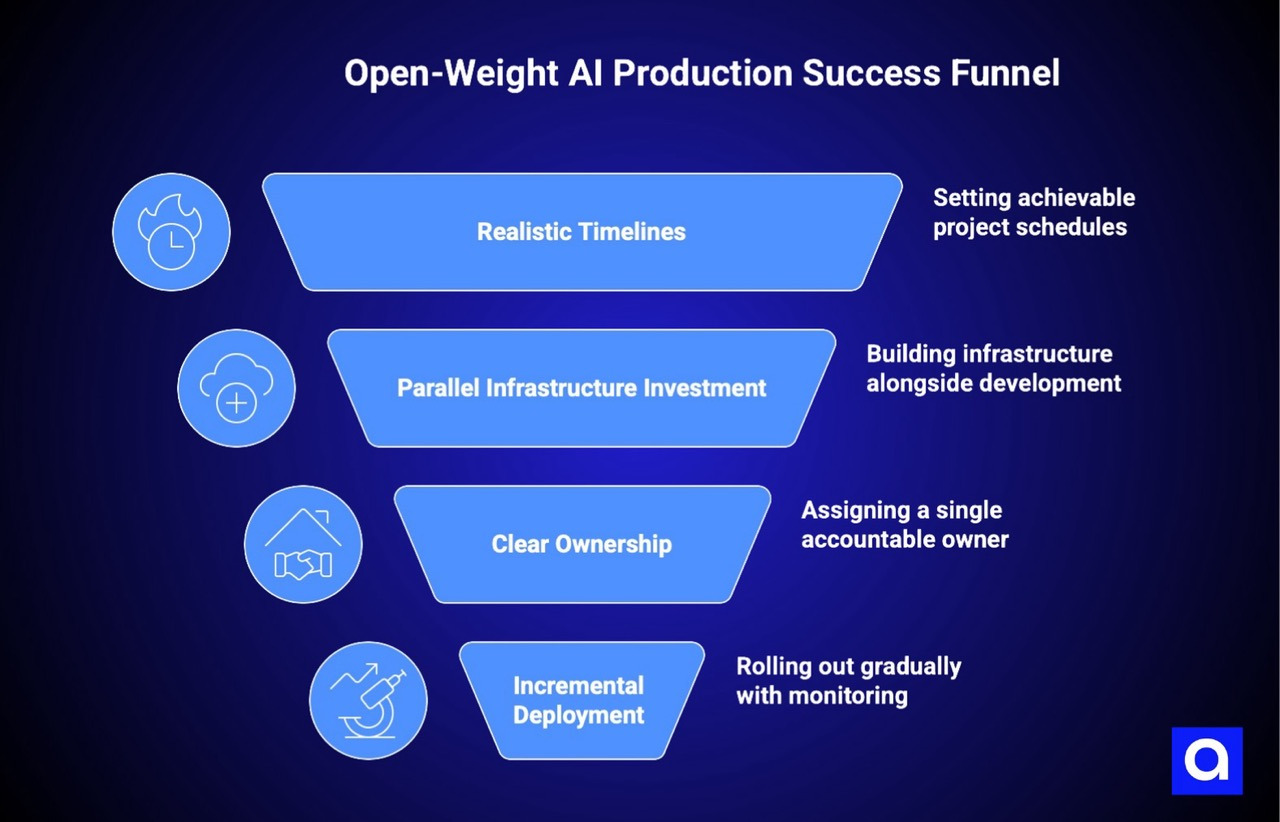

In contrast to projects that fail, successful open-weight model deployments share several common characteristics. These characteristics are not mysterious or dependent on exceptional talent; they are systematic approaches that acknowledge the real complexity of moving from prototype to production and plan explicitly to address that complexity.

Realistic timelines represent the first characteristic of successful projects. Organizations that successfully deploy open-weight models typically estimate that moving from prototype to production requires three to six months, not eight weeks.

These timelines include not only the time to build serving infrastructure but also the time to address operational requirements, implement security controls, tune performance, and gradually transition to production.

This realism about timelines allows the organization to plan resources appropriately, set realistic expectations with stakeholders, and maintain focus and momentum across the entire timeline.

Parallel infrastructure investment represents a second characteristic of successful projects. Rather than waiting until the model is finalized and then beginning to think about production infrastructure, successful organizations begin infrastructure work in parallel with model development.

This parallel work identifies infrastructure challenges early, allows solutions to be tested in controlled environments, and ensures that the team is ready to move to production quickly once the prototype achieves acceptable performance.

This approach typically involves designating infrastructure engineers to begin designing and prototyping the serving infrastructure while prototype development is still underway.

Clear ownership and decision-making authority represent a third characteristic. Successful projects have a clear owner who is accountable for moving the project from prototype to production.

This owner has authority to make decisions, to allocate resources, and to resolve conflicts between prototype requirements and production requirements. The owner might be from the research team, the engineering team, or might be someone specifically assigned to bridge the two teams.

What matters is that responsibility and authority are aligned, not split between teams with different incentives.

Incremental deployment and gradual rollout represent a fourth characteristic of successful projects. Rather than attempting to move directly from prototype to full production, successful projects implement canary deployments and gradual traffic ramps.

The system is deployed to production with small traffic volumes, performance is monitored, and traffic is gradually increased as confidence builds. This approach allows problems to be discovered and addressed while the blast radius is small.

Problems that would be catastrophic if they appeared while serving peak load are manageable when the system is serving ten percent of expected traffic.

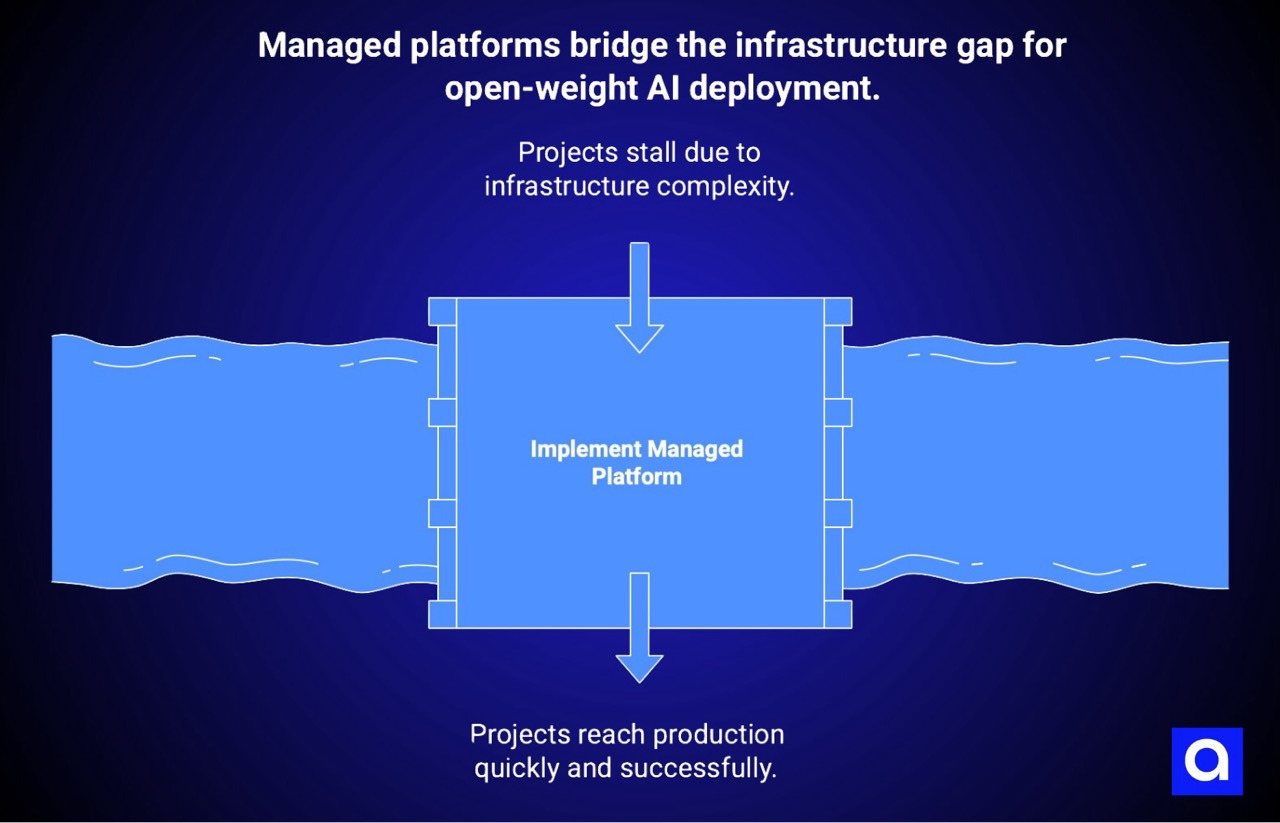

How Do Managed Platforms Reduce Time to Production for Open-Weight AI?

Many organizations attempting to deploy open-weight models encounter a gap between their infrastructure expertise and the complexity of production deployment. This gap is often the difference between projects that reach production and projects that stall. Managed platforms that handle infrastructure complexity can dramatically reduce the effort required to bridge this gap.

Managed infrastructure platforms like Valkyrie can serve as essential infrastructure accelerators for organizations deploying open-weight models. We've seen these platforms dramatically reduce time to production by handling many of the infrastructure challenges that cause projects to fail.

GPU orchestration is managed by the platform, which handles allocation of computational resources across requests, managing memory constraints, and scaling based on demand. Serving optimization is built into the platform, which implements efficient batching, latency-optimized request handling, and throughput maximization. Model versioning and updates are managed by the platform, which allows new model versions to be deployed with gradual traffic ramps and automatic rollback if problems are detected.

Beyond infrastructure, managed platforms provide operational capabilities that serve as enablers for successful deployment. Monitoring and observability are built in, providing visibility into model performance, infrastructure utilization, and emerging problems.

This monitoring allows organizations to identify issues early and respond before problems affect users. Security controls are integrated into the platform, including input validation, output filtering, and threat detection.

These controls eliminate the need for organizations to build security infrastructure from scratch. HIPAA and GDPR compliance support allows organizations deploying models in regulated industries to meet compliance requirements without implementing comprehensive compliance frameworks independently.

Cost management becomes far simpler with managed platforms because the platform operator has already optimized the cost/performance tradeoff for inference workloads.

Organizations do not need to decide whether to use GPUs or specialized inference accelerators; the platform supports multiple hardware backends and selects the most cost-efficient option. Organizations do not need to guess about utilization patterns and reserve excessive infrastructure; the platform scales automatically to meet demand.

Regional deployment options allow organizations to serve users with low latency while maintaining data sovereignty and compliance with data residency requirements.

Most importantly, managed platforms reduce the engineering effort required to reach production. An organization that would otherwise need to hire infrastructure specialists, implement serving frameworks, build monitoring and operations infrastructure, and debug operational issues can instead focus on preparing their models, integrating with the platform, and validating performance.

This shift allows organizations to reach production in weeks rather than months, and allows smaller organizations without extensive infrastructure expertise to deploy open-weight models successfully.

How to Build an Open-Weight AI Model for Production from the Start?

Organizations deploying open-weight models can dramatically improve their success rates by adopting engineering approaches that account for production requirements from the start rather than treating production requirements as afterthoughts.

This engineering discipline involves evaluating infrastructure requirements early, budgeting explicitly for production engineering, engaging operations teams from the start of the project, and seriously considering managed platforms as parts of the infrastructure stack.

Evaluating infrastructure requirements early means that organizations should not wait until the prototype is complete to begin thinking about serving infrastructure.

As soon as the team has a model that is reasonably stable and shows promise, infrastructure engineers should begin evaluating serving frameworks, estimating computational requirements, and identifying potential architectural challenges.

This early evaluation often reveals that the prototype approach cannot scale efficiently to production, which forces changes to the model architecture or training approach while the team still has flexibility to make these changes.

By contrast, discovering scaling issues after the prototype is complete often means rearchitecting the model under time pressure, which leads to poor decisions and schedule slips.

Budgeting explicitly for production engineering means acknowledging that moving from prototype to production requires substantial additional engineering effort beyond the prototype development work. Organizations should estimate that production engineering will consume as much or more effort than prototype development.

This budget should include infrastructure design, serving framework integration, monitoring and operations infrastructure, security implementation, testing and debugging, and deployment infrastructure.

By budgeting for this work explicitly, organizations can allocate resources appropriately and maintain realistic timelines.

Engaging operations teams from the start means involving people who understand production operations, reliability engineering, and operational support in the project from the beginning.

Operations engineers can identify operational challenges that developers overlook, can anticipate failure modes and reliability requirements, and can ensure that the system is designed in ways that are operationally sustainable.

In contrast, designing systems with operations teams joining only at the end often results in systems that are difficult or impossible to operate reliably, requiring substantial rework to address operational concerns.

Considering managed platforms seriously as infrastructure components means evaluating platforms like Valkyrie as potential solutions rather than dismissing them as overpriced or unnecessary.

A managed platform might not be suitable for every open-weight model deployment, but for many deployments, a managed platform dramatically reduces engineering complexity while reducing total cost of ownership.

The cost comparison should be honest: not just the platform subscription fee, but the engineering time saved, the reduced need for specialized expertise, and the faster time to production. For many organizations, the engineering time saved by using a managed platform justifies the subscription cost many times over.

What Does The Production-Ready Infrastructure for Open-Weight Models Look Like?

The fundamental insight that distinguishes successful open-weight model deployments from failed ones is recognizing that prototypes and production systems are not incremental steps on a continuum but rather different categories of systems with different constraints, requirements, and engineering approaches.

The engineering discipline required to build production systems is not a small extension of prototype engineering but rather a fundamentally different approach. The infrastructure required for production is not a simple scaling of prototype infrastructure but rather a different set of systems with different architectural principles.

Organizations that deploy open-weight models successfully do so by embracing this distinction explicitly.

They allocate adequate engineering resources, create realistic timelines, maintain focus and organizational support, and leverage managed platforms and infrastructure solutions that handle the complexity that most organizations are not equipped to manage in-house.

They recognize that the path from prototype to production is long and complex, but that the challenges are well-understood and have been solved by organizations that came before them.

The industry is moving toward solutions that acknowledge this complexity and reduce it for organizations attempting to deploy open-weight models. Managed platforms, specialized serving frameworks, and infrastructure tools that collectively address the challenges that cause prototype-to-production projects to fail are becoming increasingly mature and accessible.

Organizations that deploy open-weight models going forward will do so in an ecosystem where production deployment is far more tractable than it was for early adopters.

The organizations that succeed will be those that take advantage of these solutions, that plan explicitly for production requirements, and that avoid the assumption that a successful prototype automatically scales to successful production.

Move from prototype success to production-ready AI, without rebuilding everything from scratch.

Through our dedicated AI development services, we help organizations deploy open-weight AI systems with regional data residency, HIPAA and GDPR compliance, and infrastructure designed for real-world scale. From serving architecture to secure production rollout, we help teams close the gap between demos and dependable systems.

Contact Azumo to discuss how to deploy open-weight AI in production with confidence.

.avif)